Much has been written about the slowness of the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry. Slowness to adopt new digital technologies. Slowness to embrace new construction methods. Slowness in delivering projects. Depending on whom you ask, the root cause varies. Some attribute this slowness to a lack of digital skills. Others point to the legal and regulatory framework in which we operate. Others point to the inbuilt incentives to be inefficient through change orders and variations. While these are all contributing factors, I would like to look at another factor – command-and-control management practices around how decisions are made. The message is simple. We need to stop working in the business, and start working on the business.

The scenario

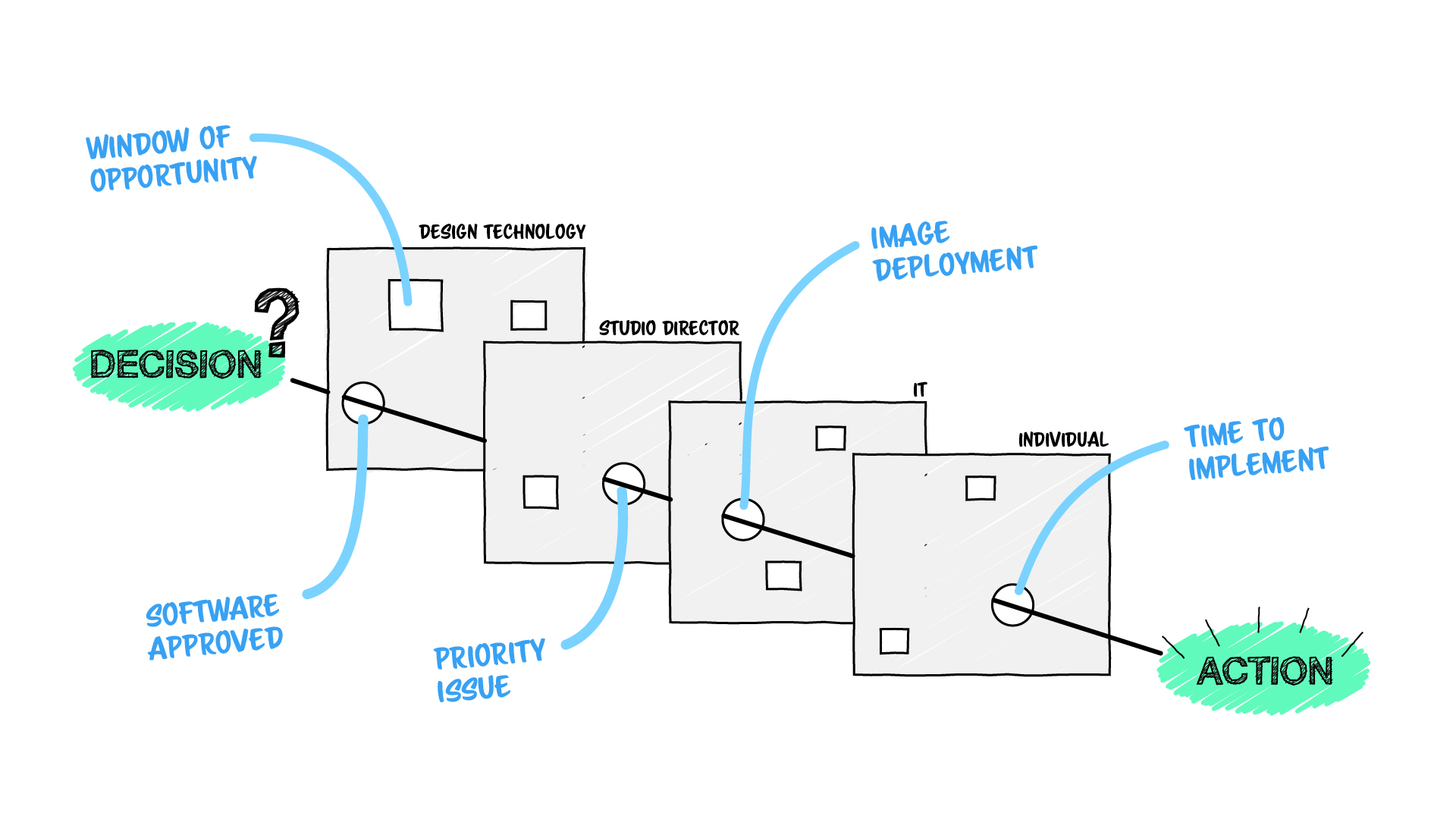

Consider a simple request for a new piece of software in your organisation. The software is only $10 and will automate a task you must do repeatedly. You remember how the company continuously talks about being more innovative, and in your mind, it’s a no-brainer.

But you don’t have administration privileges, so even if you bought the software, you couldn’t install it. No, the decision needs to be escalated to the Design Technology department. Unfortunately, the software isn’t on the approved software list, and it would be yet another tool they would have to learn and support. So, the request is brushed off.

Determined, you escalate the matter to the studio directors for approval. However, the appropriate director is consumed with business as usual, and the issue isn’t on their priority list. Weeks, sometimes months, pass, and the matter still isn’t resolved. Then, the same task resurfaces on a new project, and the director asks, “I thought we already have software that does this?” And you reply, “No, the issue was never resolved.” And so the director approves the purchase then and there and sends the necessary make it happen email. But the issue is far from resolved.

The decision-making war of attrition

The Information Technology (IT) team raise concerns. Sure, we can purchase the software, but we’re currently busy with other projects. Weeks, sometimes months, pass until the same task resurfaces like a bad itch that won’t go away. You remind IT that this issue is still outstanding, but the person you were dealing with has left the organisation. So you brief the new person and politely ask them to resolve the issue as soon as possible, which they do. You receive an email from IT saying that the software is ready to be deployed and will be pushed to all staff in the next image…in a couple of weeks.

Eventually, the war of attrition is over, and the software is finally deployed. But everyone in the process is exhausted and somewhat bitter about the outcome. The end-user is so frustrated that they don’t even care anymore. The Design Technology team is annoyed that the decision went over their heads. The IT team is annoyed that they got pulled off from their current project. And the studio director is annoyed at how slow it took to resolve a simple issue. Much like a moon landing, all the stars needed to align just to make it happen. But no one questions the process – that is just how we’ve always done it

One-size decision-making

This story may sound extreme, but a poor decision-making framework is pervasive, particularly in large AEC organisations. And it isn’t just limited to software. The issue plagues all facets of business, at all levels, and all departments. More often than not, what holds up a decision has less to do with obtaining consent and more to do with the decision-making process itself. Why, then, does this happen, and what can organisations do differently?

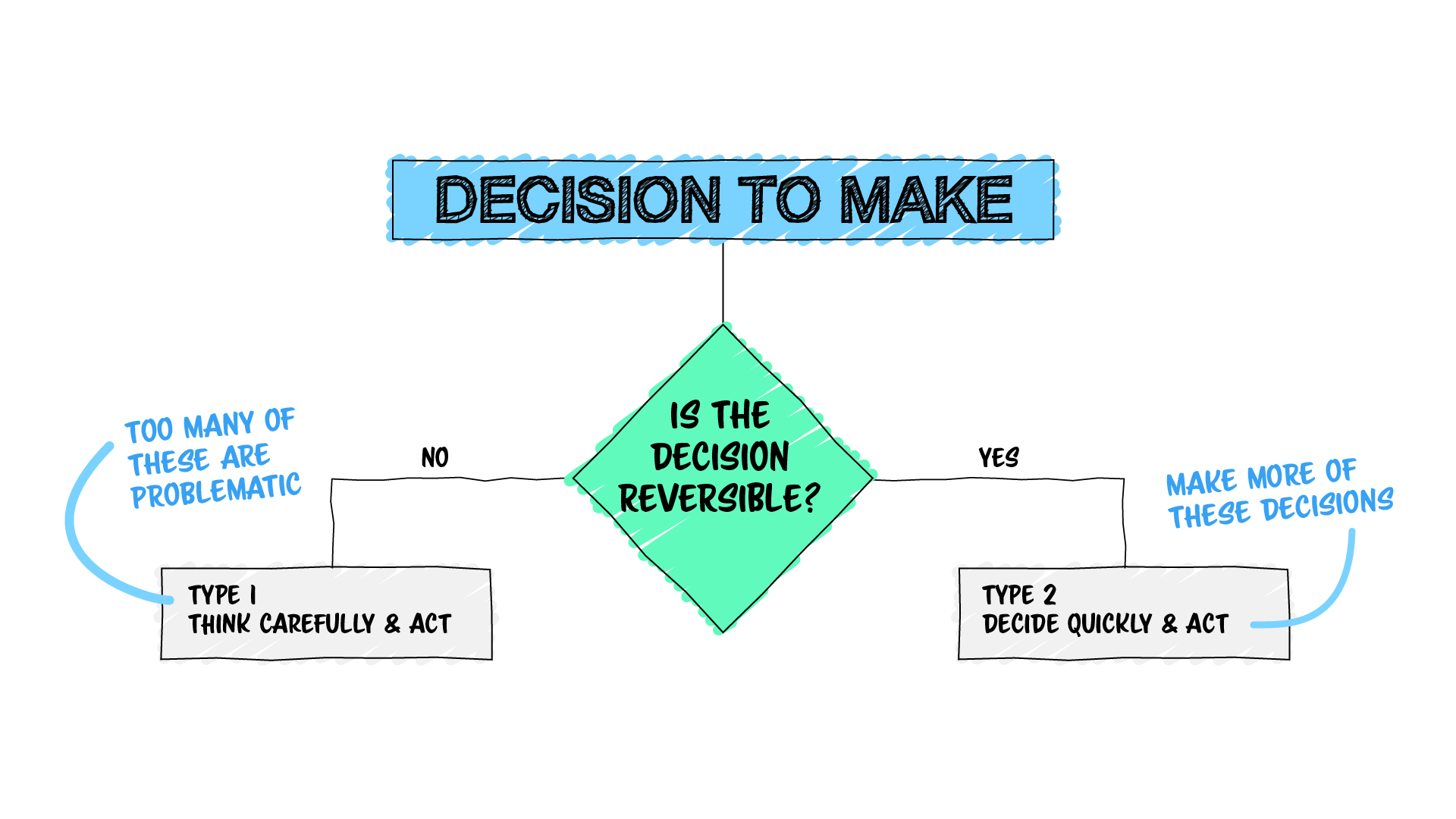

Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, describes that one of the most common pitfalls for large organisations is one-size-fits-all decision-making. He makes the distinction between what he terms Type 1 decisions and Type 2 decisions:

Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible – one-way doors – and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation…We call these Type 1 decisions. But most decisions aren’t like that – they are changeable, reversible – they’re two-way doors…Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgements individuals or small groups.

Jeff Bezos1

Bezos continues why this distinction is important:

As organisations get larger, there seems to be a tendency to use the heavy-weight Type 1 decision-making process on most decisions, including many Type 2 decisions. The end result of this is slowness, unthoughtful risk aversions, failure to experiment sufficiently, and consequently diminished invention.

Jeff Bezos2

Not choosing is still a choice

Some may be tempted to dismiss this theory as merely a soundbite. But there is scientific backing to it. As discussed in our Identifying innovation opportunities article, it is well known that cognitive biases lead to poor decision-making. And one of the best ways of eliminating cognitive biases, is a technique called delayed intuition. As Daniel Kahneman explains, “Intuition need not be banned, but it should be informed, disciplined, and delayed.”3 In other words, taking your time is the right approach when a decision is consequential.

However, at the other end of the spectrum is analysis paralysis. Research shows that “presenting people with a wide array of options doesn’t liberate them: it paralyses them.”4 This is known as the paradox of choice – If we overthink a decision, we most likely fail to arrive at any decision. However, as existentialism has shown us, not choosing is still a choice. And it is this failure to make decisions quickly that is costing organisations.

as existentialism has shown us, not choosing is still a choice.

One-size decision-making in the AEC industry

Reflecting on our earlier scenario, it is clear that the decision to buy the software was vastly inconsequential. It was low cost, low risk, and easily reversible—a classic type 2 decision. In fact, if we consider all the overhead time spent just to arrive at the decision, the cost of that alone far exceeds the cost of purchasing the software. What was needed, therefore, was a quick decision and action by an empowered individual or small group.

To be clear, I’m not advocating a free-for-all where employees have unrestricted IT administrative privileges. Absolutely, checks should have been undertaken to ensure malware wasn’t inadvertently installed. However, the point is that any type 2 decision, regardless of the topic, needs to be decided and acted upon quickly. For example, the IT or Design Technology team could have easily treated the request as a pilot project or experiment, whereby the software was purchased and locally installed on a single PC. If successful, the software could be rolled out to the entire organisation via a deployment at a later date. If unsuccessful, the software could have simply been uninstalled. No harm done.

So why, then, didn’t this happen? The most likely explanation is that the organisation has been structured and managed in a way that fails to enable individuals to make decisions. In other words, the organisation is using command-and-control management.

Taylorism

The origin of command-and-control management can be traced back to 1911 when Federick W. Taylor first advocated Scientific Management.5 Known as Taylorism, it uses scientific methods to analyse the most efficient production process to increase productivity. Taylor’s scientific management theory argued that workplace managers should develop the proper production system to achieve economic efficiency. His four scientific management principles include:

- Select methods based on science, not rule of thumb. Rather than allowing each individual worker the freedom to use their own rule of thumb method to complete a task, you should instead use the scientific method to determine the one best way to do the job.

- Assign workers jobs based on their aptitudes. Instead of randomly assigning workers to any open job, assess which ones are most capable of each specific job and train them to work at peak efficiency.

- Monitor worker performance. Assess your workers’ efficiency and provide additional instruction when necessary to guarantee they are working productively.

- Properly divide the workload between managers and workers. Managers should plan and train, while workers should implement what they’ve been trained to do.

Command-and-control as a management system worked well in highly predictable environments, like factory assembly lines, as was common in the 20th century. However, command-and-control leadership styles disempower people and reduce autonomy.6 In today’s knowledge economy, work is too complex and ambiguous for a leader to maintain control. But that doesn’t stop us from trying.

Command-and-control BIM

Take BIM, for example. Somewhere along the line, BIM stopped being about advancing the AEC industry and instead became focused on self-preservation. We were told staff couldn’t do specific tasks because they would break the model. No, we needed a gatekeeper through which all information must flow. We gave them the title BIM manager, and manage they did – fighting fire after fire and writing endless standards and best practices to prevent issues from happening again. But like a hot, climate change-induced summer in Australia, the fires kept coming. Burnt out and disillusioned by a lack of visible progress, they enter the revolving door that is BIM recruitment. One out, one in, only for the cycle to repeat ad nauseam.

It’s time we stop perpetuating this command-and-control management style. By focusing on compliance, we can’t expect people to take responsibility for their actions. And if people don’t take responsibility for their actions, the fires will keep coming. Put simply, we need to be focusing on teaching people to think, not policing compliance. And this begins by embracing effective leadership strategies that empower staff to make the correct decisions for the organisation.

When best isn’t best

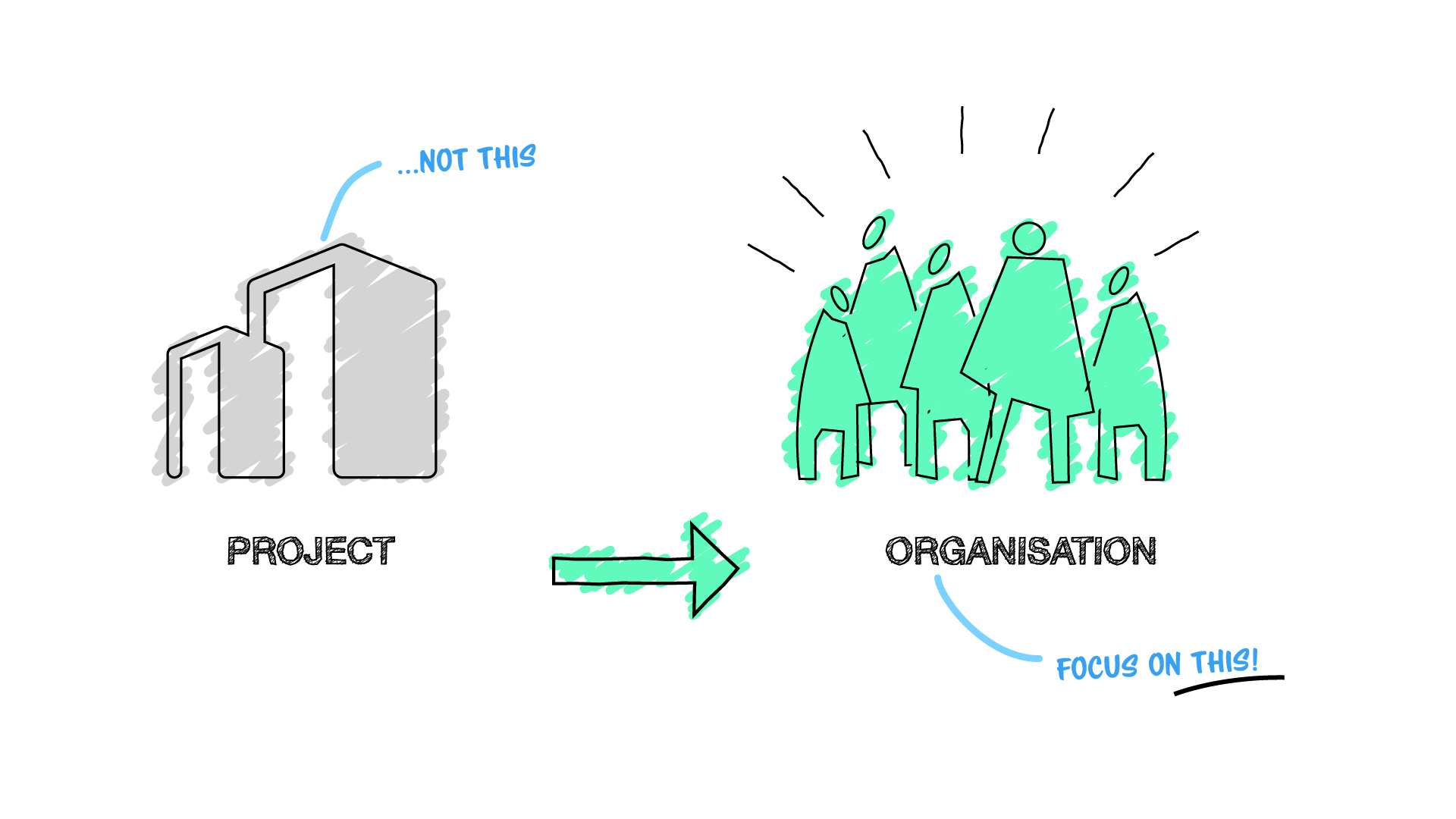

The key point here is “for the organisation”. Not best for the project. Not best for the individual. But best for the organisation. In our scenario, each protagonist considered only their domain, applying best practices so as to be as efficient as possible. Concerned that staff would install malware, the IT department restricted administration rights. Wanting to limit the amount of software they need to support, the Design Technology department blocked access to new software. Wanting to standardise configurations, the IT department delayed deployment.

However, taken as a whole, these best practices were incompatible. While you took the initiative to foster change, you didn’t have the authority. It was only once the director took a holistic view of the problem and determined that the trade-offs were in the organisation’s best interests that a resolution was reached.

To be clear, I am not suggesting a free-for-all where staff can do as they please. Every organisation needs checks and balances to prevent corporate malpractices. But I am suggesting the elimination of command-and-control managerial hierarchies in favour of wider decision-making power. As Dave Grey sums up nicely in The Connected Company, “There is no way for people to respond and adapt quickly if they have to get permission before they can do anything.”7

Project-centric decision-making

Of course, the issue here goes far deeper than mere decision-making. It goes to the heart of the profession and our deeply ingrained ways of working. I’ve written extensively about my belief that the core reason for many of the AEC’s issues is its project-based nature. A project-based approach has many downsides, not least of which is that organisations reward managers for achieving short-term objectives that are bad for the organisation.

It’s why we have the endless debate about overhead staff – that is, employees who can’t be charged to a project. It’s why project managers will elect to do something inefficiently, even though if they invested a bit more time and energy, everyone in the organisation could benefit. It’s why principals and directors jostle to have preferred team members, causing inter-organisation silos. But most importantly, it is why staff who want to invest in the future, even if that investment cannot be easily measured, leave organisations.

From command-and-control to trust and transparency

Before an individual or small group can make the best decision for the organisation, they must be fully aligned with the organisation. But this is hard. It takes a lot of work to ensure that people work in the organisation’s interest rather than their own. And it is evident that many organisations struggle with this. From our experience working with AEC organisations, most staff are unable to articulate an organisation’s why, be it a tagline, purpose or belief, let alone its strategic priorities. Studies at Harvard Business School show that only 7% of employees “fully understand their company’s business strategies and what’s expected of them in order to help achieve the common goals.”8 How, then, can employees possibly determine what is in the organisation’s best interest if they don’t know its priorities? Put simply, they can’t.

One could forgive the command-and-control approach if organisations were upfront about how they were managed. However, all too often, we witness the illusion of empowerment. How many organisations claim and heavily promote being innovative and leaders in digital technology? Almost all. How many individuals in these positions, such as Chief Technical Officers or Director of Design Technology, are equity shareholders and have a genuine seat at the table in how the business is run? Almost none. Most are relegated to merely advisors. And this is a huge missed opportunity.

The illusion of empowerment

We don’t hire smart people to tell them what to do. We hire smart people so they can tell us what to do.

Steve Jobs

In his book Superusers, Randy Deutsch touches on many of the issues surrounding the lack of career progression for design technology specialists in conventional AEC practices.9 But the issue is bigger than just design technology. It is about a general lack of empowerment across all facets of the profession.

One practice director at a large international architectural firm recently told me, “They trust me to design, so long as that part of the building is not visible.” Consider that for a moment. One of the organisation’s leaders, responsible for running multi-million dollar projects, isn’t trusted to make simple, everyday design decisions. The approach is not just demoralising; it is also highly ineffective. Again, the issue is not about operating completely autonomously without oversight. It is about creating an engaged and empowered workforce. As Peter Drucker famously said, “Authority without responsibility is tyranny, and responsibility without authority is impotence.”10

Human vending machines

At play here is command-and-control management whereby employees are treated like vending machines: “They flip their instructions at us like a coin and then wait, tapping their foot, until we give them exactly what they want.”11 While this approach might have passed in a 20th-century factory assembly line, in today’s knowledge economy, it is a recipe for disaster.

Andy Grove, the former chairman and CEO of Intel, coins this managerial medalling negative leverage. He defines negative leverage as managerial activities that reduce the output of an organisation. He describes how this occurs: “The subordinate will begin to take a much more restrictive view of what is expected of him, showing less initiative in solving his own problems and referring them instead to his [or her] supervisor…The output of the organisation will consequently be reduced…”.12 And we witnessed just that in our scenario, whereby each protagonist showed little initiative and left the true problem-solving to the director. In other words, the employees were working in the business. What is needed, however, is employees to work on the business.

According to Peter Drucker, the professional employee “needs rigorous performance standards and high goals…But how he [or she] does his [or her] work should always be his [or her] responsibility and his [or her] decision.”13 How, then, can organisations define and measure output by knowledge workers without resorting to Taylorism?

A culture of discipline

If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

By far one of the most successful management techniques is known as Objectives and Key Results (OKRs). First proposed by Andy Grove as Management by Objectives(MBO), it was later refined by venture capitalist John Doerr. As an early investor in Google, Doerr introduced the concept of OKRs as “a management methodology that helps to ensure that the company focuses efforts on the same important issues throughout the organisation.”14 In other words, it is a structured approach to organisational goal-setting and alignment.

Objectives are simply what is to be achieved. Key Results benchmark and monitor how we get to the objective. Effective key results are specific and time-bound, but most importantly, they are measurable and verifiable. The major benefit of OKRs is that they empower employees to work on the business in an aligned way. As Jim Collins describes, “When you have disciplined people, you don’t need hierarchy. When you have disciplined thought, you don’t need bureaucracy. When you have disciplined action, you don’t need excessive controls.”15 Whether an organisation chooses to adopt ORKs or not is not critical. But what is critical is that we move away from outdated management practices that disempower people by focusing solely on compliance.

Conclusion

For too long, the AEC industry has adopted a command-and-control management practice, specifically regarding decision-making. While this approach might have worked in a 20th-century factory assembly line, it is a recipe for disaster in today’s knowledge economy, resulting in reduced output, a lack of agility and a demoralised workforce. By focusing on compliance, we can’t expect people to take responsibility for their actions. And if people don’t take responsibility for their actions, the fires will keep coming. The message is simple. We need to stop working in the business and start working on the business.

References

1 Bezos, J. (2021). Invent & wander: The collected writings of Jeff Bezos. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, p.143.

2 Bezos, J. (2021). Invent & wander: The collected writings of Jeff Bezos. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, p.143.

3 Kahneman, D. et al. (2021). Noise: A flaw in human judgment. William Collins, London, p.373.

4 Schwartz, B. (2004), The paradox of choice: Why more is less. Harper Collins, New York, p.xi.

5 Taylor, F. (1911). The principles of scientific management.

6 Frahm, J. (2021) Change leader: The changes you need to make first. Jennifer Frahm Collaborations, Melbourne, p.73.

7 Gray, D. (2014). The connected company. O’Reilly, Sebastopol, p.148.

8 Kaplan, R. & Norton, D. (2001). The strategy-focused organisation: How balanced scorecard companies thrive in the new business environment. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

9 Deutsch, R. (2019). Superusers: Design technology specialists and the future of practice. Routledge, New York.

10 Drucker, P. (1946). Concept of the corporation. John Day Co, New York.

11 Amaechi, J. (2021). The promise of giants. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London, p.114.

12 Grove, A. (2015). High output management. Vintage Books, New York, p.58.

13 Drucker, P. (1954). The practice of management. Harper & Row, New York, p.336

14 Doerr, J. (2018). Measure what matters. OKRs – the simple idea that drives 10x growth. Penguin Random House, London, p.7.

15 Collins, J. (2001). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap…and others don’t. Random House, London, p.13.