Standardise, standardise, standardise goes the beat of the modular construction drum. Standardisation is so indoctrinated in modular construction’s ethos that it permeates not just into the design and manufacturing but critically to the business model as well. Like a car manufacturer, modular construction’s business is premised on supplying standardised solutions at a high volume to lower costs. However, as many failed modular organisations demonstrate, industrialised construction is not the same as manufacturing.

Construction generally lacks the critical mass required for a volume-operation business model. There is simply too much variation. Every site will likely have a unique aspect, shape, topography and soil conditions. Lots on the same street will likely have different planning controls. Some locations will require seismic and flood mitigation, while others must be designed to withstand hurricanes and tornadoes. And building codes often aren’t even unified at a national level, let alone at an international level. All of this is before considering market preferences. So what’s the alternative?

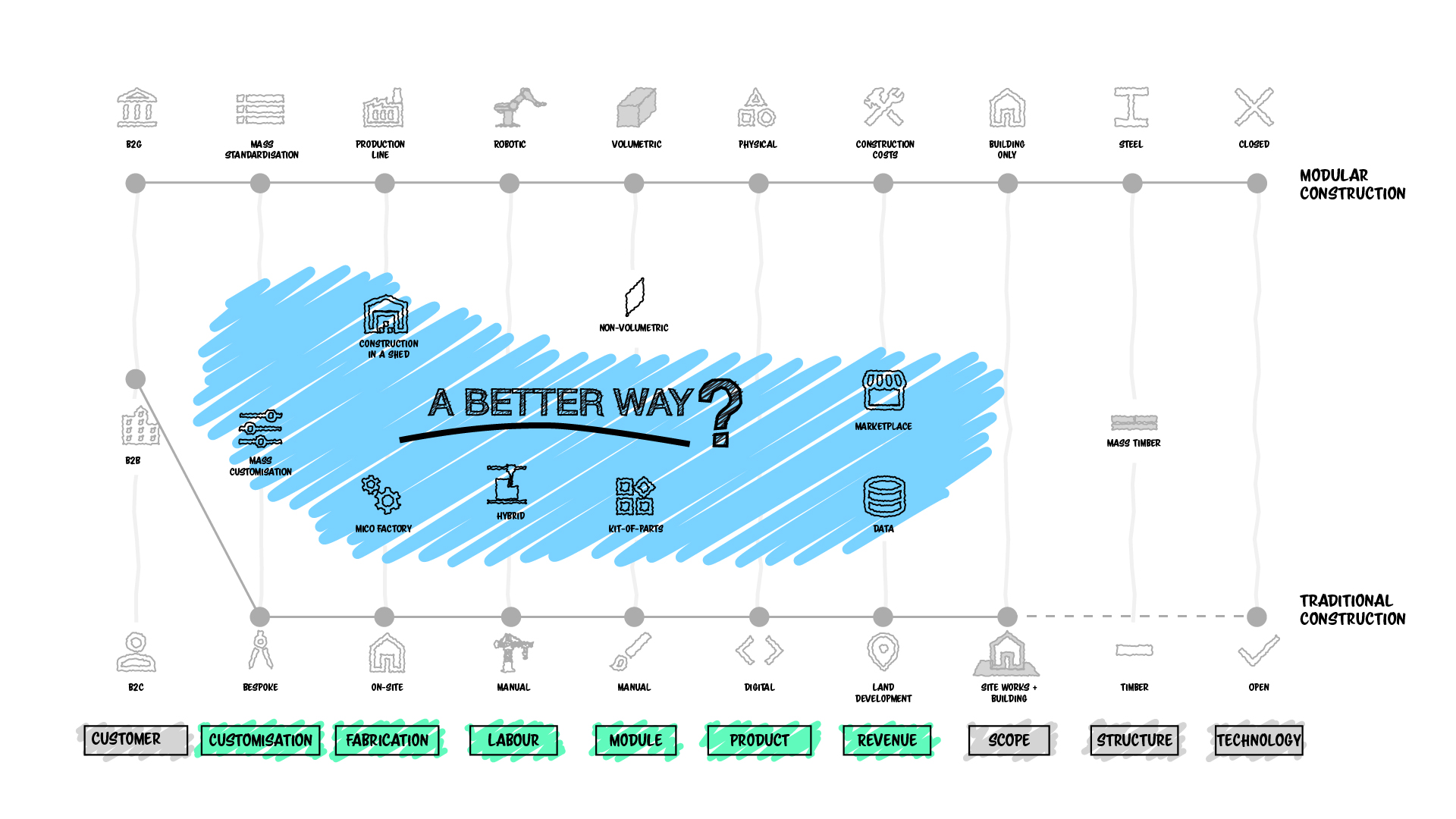

It is clear that many new startups are exploring alternate business models, which are neither traditional construction nor modular construction, but somewhere in between. This grey area is unchartered territory but may be the key to finding a viable and scalable solution.

Business model innovation

Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.1

A business model describes how a company plans to make a profit and defines who the customer is, what the customer value proposition is, and what the key resources and processes are. Different permutations result in different business models, and these nuances are critical.

Uber and Airbnb, for example, make their profits (but mostly losses) from digital platforms that connect people. Or consider the razors/blades business model where the initial product is sold at a discount or loss, but which locks customers in, requiring them to make high-volume repeat purchases for consumables, such as print cartridges or disposable razor blades. Or even Big Tech, such as Facebook or Google, whose data-into-assets model offers free apps but make their money by selling your personal data.

Standardise, standardise, standardise

It is clear that modular constructions’ dominant business model to date has been standardisation – providing lower-cost standardised solutions at a high volume. Take this quote, for example, from Helena Lidelöw, Chief Technical Officer (CTO) of US-based Volumetric Building Companies (VBC):

As if code requirements were not enough, you can add self-inflicted behaviour to the bucket of ‘repetition destroyers’. The term ALMOST the same is a killer in this category. When an architect says ‘these units are the same, I just stretched the width a little to make it fit’ that is directly affecting the downstream outcome.

Because, what happens under the hood is that all your electrical wiring just got different wire lengths, your plumbing runs shifted, if you use trusses they now have a different length, and the structural studs have different positions so the sheathing needs to be cut and fastened at new locations. A shop drawing team could very well opt to start over with their work due to the many changes that actually result from ‘just stretching the width to make it fit’.

Helena Lidelöw, Volumetric Building Companies 3

This quote highlights two things. First, it reveals VBC’s bias for an optimised manufacturing process over an optimised design – the polar opposite of most architecturally designed buildings. Second, it shows that the design process is not automated; even the slightest change means starting over from scratch. This is not to say this business model is wrong. Just that standardisation is the business model, which requires high volume for this to succeed.

Maybe VBC does have sufficient volume to make standardisation successful. After all, they have been around for fifteen years, so they must be doing something right. But at the same time, the high failure rate shows that many others don’t have the volume needed to make standardisation work. With this in mind, why are so many fixated on standardisation as the dominant business model?

Standardised designs

One only has to look at the numerous government agencies worldwide attempting to “solve the housing crisis” to answer this. In Australia, the New South Wales government is launching a pattern book of endorsed modular building designs, and Queensland is encouraging modular construction via the Homes for Queenslanders initiative.4 In the United Kingdom, Homes England has mandated that 25% of homes be built using MMC as part of the Affordable Homes Programme. In Canada, British Columbia recently announced its Standardised Housing Design Project – a series of pre-approved, standardised designs to enable developers to create housing faster.5 Additionally, the City of Fredericton in New Brunswick is offering a CA$20,000 grant per modular home under the city’s new manufactured housing grant scheme.6

There appears to be no end in sight, at least for the foreseeable future, to the governmental wet-nursing of MMC. And that is fine. By all means, advocate and try new solutions. But the question remains: Will these incentives be effective? Unfortunately, the answer is probably not.

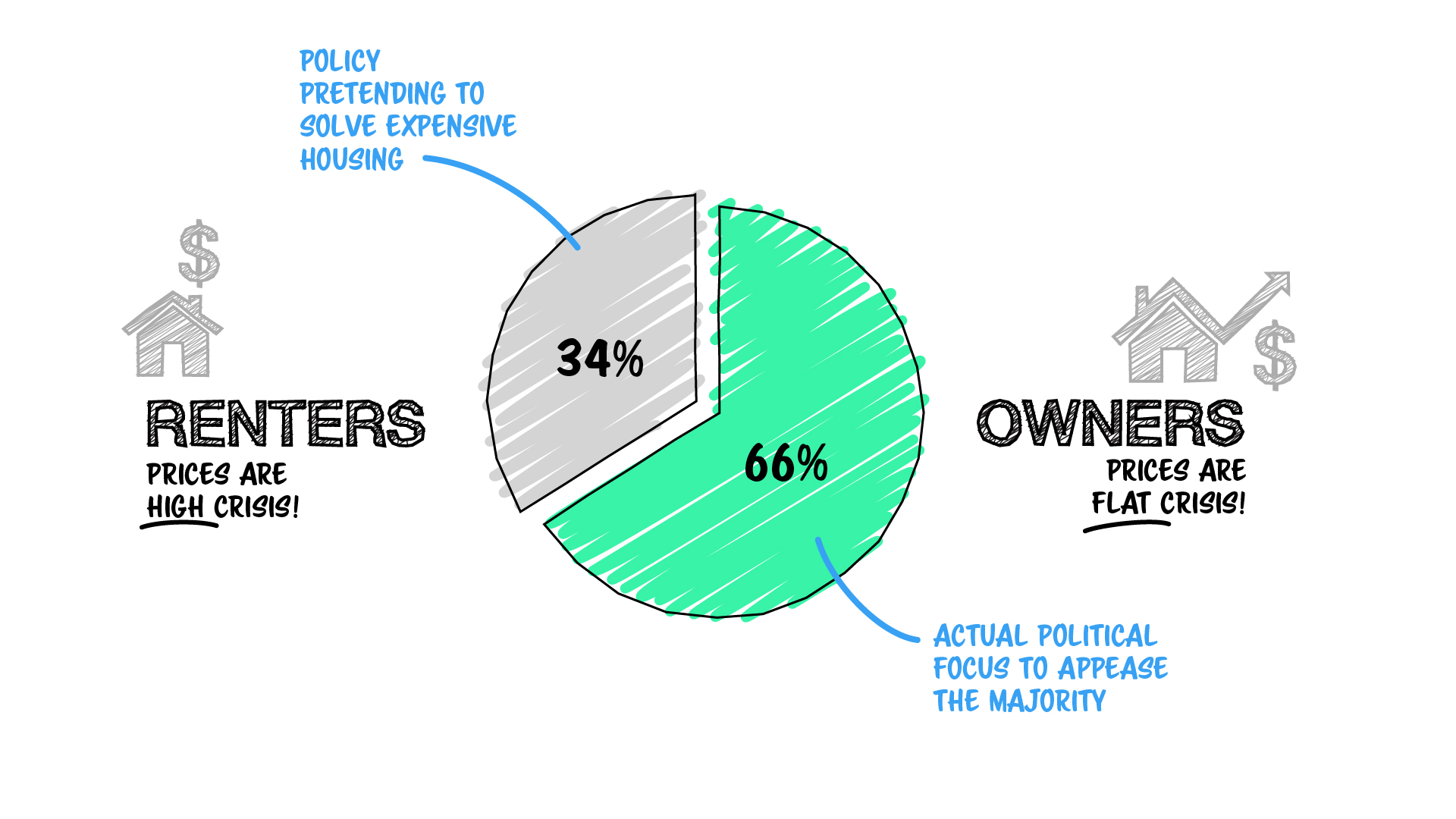

Political placebo

The economist Cameron Murray has argued, “[political] policies pretend to solve the problem of expensive housing but avoid the political costs of creating winners and losers due to the symmetry of property markets.”8 Consider homeownership, which in Australia is 66%. In the UK, it is 64%. And in the USA, it is 66%. Quite simply, the political policies fall heavily on the side of the majority, who, in this instance, benefit from higher housing rents and prices. In other words, it is not in most politician’s interests to “solve” housing, only that they appear to be trying to solve it. One only needs to look at the staggering number of housing system reports and inquiries that have occurred over decades. Lots of talk, very little action.

Feasibility ≠ viability

The second reason that government intervention is likely to be ineffective is that it doesn’t solve the fundamental issue of establishing a scalable and profitable business model. Astonishingly, despite many stakeholders proclaiming MMC as the panacea, modular organisations continue to fail. Why?

Quite simply, just because a construction method is feasible doesn’t mean it is viable. Governments come and go, and so too do policies and frameworks. Only through broader free market adoption can a sustained pipeline be achieved. The point is, trying to create a viable business model through Mass Standardisation + Mass Production is just one solution and arguably not the best.

Modular construction’s business model

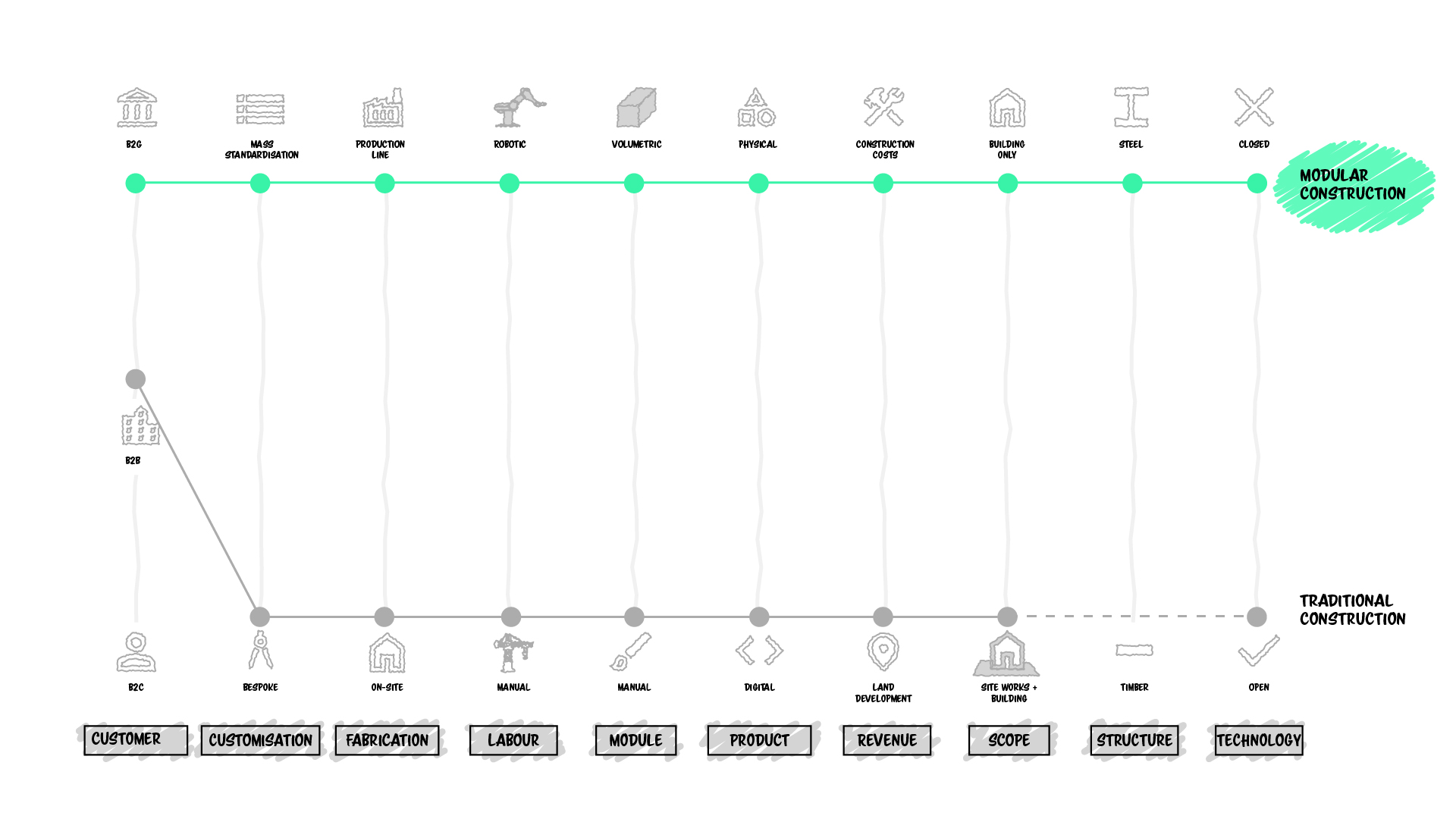

Within an industrialised construction approach to building, a range of biases collectively form the business model. For example:

- Customer – Business-to-government (B2G), business-to-business (B2B) or business-to-consumer (B2C)?

- Customisation – Mass standardisation, mass customisation or bespoke?

- Fabrication – Production line, construction-in-a-shed, micro-factory or on-site?

- Labour – Robotic, hybrid or manual?

- Module – Volumetric, non-volumetric, kit-of-parts, or manual/non-standardised?

- Product – Physical or digital?

- Revenue – Building costs or land development?

- Scope – Building only or site works plus building?

- Structure – Steel, concrete, mass timber or timber?

- Technology – Closed or open?

These biases can be mapped, highlighting the different strategic approaches. Take, for instance, the classic volumetric modular approach, which most closely aligns with Henry Ford’s production line approach to manufacturing. It looks something like this.

The customers are often governments, such as schools or housing associations, or businesses with large pipelines, such as hotels or student housing. The design is standardised as much as possible and fabricated off-site in a large, ideally automated factory. While in-house digital tools solutions may have been developed to assist the process, the contractual deliverable is a physical object in the form of a (partial) building. Finally, the revenue model is based on reducing the construction costs through low margins but high volume. These biases all align with the business model, which aims to provide lower cost standardised solutions at a high volume.

It can be easy to become enamoured with automated production lines and big volumetric boxes being craned into position. But what separates manufacturing from construction, above all else, is not economies of scale but something far more primitive—land.

Building as financial instruments

Land monopoly is not the only monopoly which exists, but it is by far the greatest of monopolies – it is a perpetual monology, and it is the mother of all other forms of monopoly.

Winston Churchill, 1909

Almost a decade ago, OMA partner Reinier de Graaf wrote, “A building is no longer something to use, but to own – with the hope of increased asset-value, rather than use-value, over time. Buildings become part of an economic exchange cycle: conceived for the lowest possible cost, traded for the highest possible sum.”9 In a separate article written in 2015, he highlights Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation as a case-in-point.

Built in 1952 with the belief of low-cost, universal standards of living for all, units were being sold for €151,000 (for a 31 m2 studio), €350,000 (for a three-bedroom flat) and €418,000 (for a four-bedroom flat). He goes on to note that the average annual wage in France is €30,300, allowing a maximum mortgage just shy of €120,000.10 In other words, a 72-year-old decaying Brutalist building, stripped of all ornament and designed for the masses, is unaffordable for the average French citizen. And we can find similar results worldwide.

Not far from where I write this, a one-storey 1920s brick bungalow in Tamarama (just south of Bondi Beach in Sydney) recently sold for A$45m. The original owner purchased the property for $18,000 in 1959. The house was more or less as it was when it was first constructed. It wasn’t majestic or prestigious, just an ordinary brick house you would find anywhere across Sydney.

So why, then, the massive price increase? Quite simply, it highlights rule number one of property development: Location, location, location. In other words, where a building is located is the one thing above everything else that affects its value.

Structures they build or land it sits on?

In the age of Neoliberalism, where housing has stopped being a basic human right and instead has become a financial instrument, the value created by property development will always trump construction efficiency. This topic very much came to light in the recent report, Driving change in the UK housing construction: A Sisyphean task?

In the report, Dr Suzanne Peters and Professor Jonatan Pinkse from the University of Manchester note, “Factory-produced homes promise quality, speed and scale, but the firms delivering this approach – typically new entrants – struggle to realise a viable business model.”11 But more importantly, the modular construction firms under the study “are expecting profits from the structure they build, rather than the land it sits on.”12 Conversely, traditional house builders, as one government official described:

[are] in the business of selling little pieces of land for large amounts of money and putting a house on. It is an inconvenient process of making it worth something to a consumer. The house is an accidental requirement as opposed to what their business is. Their business is taking land through planning and getting large amounts of value for all that, that small parcel. And which is why the product on top of it is the minimum product possible to achieve that outcome.13

The report’s authors sum up the issue succinctly:

A fundamental issue is that the construction of the structure of a house is a relatively small portion of the overall housing development process and not always where the profits are made. The business models are quite unique in this respect. For private sector developers, profits are largely in gains from acquiring the land and attaining approvals for new developments. For social housing contractors profits are indeed in construction but the structure is only one part of the project and – when MMC is used – a large portion of that is outsourced.36

A business model predicated on improving construction costs will always be hard-pressed to compete against a business model based on land appreciation. So what is the alternative?

A bigger piece of the pie

To date, the industry’s approach to industrialised construction has focused on taking a bigger piece of the pie. This is reflected in huge capital investment, the preference for volumetric construction, and the approach to Intellectual Property (IP). But even with this approach, we are witnessing a shift away from standardisation as a business model.

Canada-based Intelligent City has embraced mass customisation, developing a (closed) software system to “standardise process, not parts”. German-based Gropyus is seeking to save on construction costs via automated manufacturing, as well as generating revenue from digitalised property and facility management, a data-into-assets business model.

Making the pie bigger

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Albert Einstein

But another approach is to make the pie bigger. As John F. Kennedy famously said, “A rising tide lifts all the boats,” and it is clear that many startups are exploring what this means in terms of business models. Think distributed knowledge, micro-factories, software platforms, and common kit-of-parts.

USA-based Assembly OSM is developing what they term “post-modular construction,” which leverages a distributed supply chain of components. These components are then passed on to an ecosystem of fabricators, who create the subassemblies. Finally, these subassemblies are combined to develop volumetric modules, which a general contractor erects.

UK-based Automated Architecture (AUAR) is creating an ecosystem of automated micro-factories. This business model provides software and hardware to form a hardware-as-a-service, industrialised construction without the high upfront costs of a large factory. Similarly, Facit Homes recently launched Facit Technology, their on-site micro-factory.

UK-based Akerlof is developing a kit-of-parts strategy for the UK’s Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. In Australia, research body Building 4.0 CRC is working with Homes NSW to develop a kit-of-parts for medium-density social housing. Schools Infrastructure NSW also pursued a similar kit-of-parts approach as part of their MMC integrator initiative. These approaches signify a shift from a business model based on pipelines to one based on platforms.

Conclusion

Distributed knowledge, micro-factories, software platforms, and kit-of-parts offer alternative ways for industrialised construction to succeed at scale. Coupled with business model innovation, they may also prove to be viable. Time will tell if this proves true. But in any case, it is refreshing to see organisations explore new business models rather than the well-trodden standardise, standardise, standardise path.

As the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote, “The task is not so much to see what no one has yet seen but to think what nobody yet has thought about that which everybody sees.” Certain things, once seen, become really hard to unsee, and as soon as someone cracks a viable business model for industrialised construction, in whatever form it may take, it will be accepted as day follows night. But until then, the challenge remains—what is the best business model to achieve industrialised construction?

References

1 Goodwin, T. (4 Mar 2015). The battle is for the customer interface. TechCrunch.

2 Adapted from: Johnson, M. et al (2019). Reinventing your business model. In HBR’s 10 must reads: On business model innovation. Harvard Business Review, Boston, pp. 34-35.

3 Lidelöw, H. (Jun 2023). While I was hiking in Yosemite last weekend. LinkedIn.

4 NSW Government. Pattern book of housing design.

5 Hixson, R. (17 Nov 2023). B.C. begins project to create standardized home designs. In Site News.

6 Build Offsite. (24 May 2024). Grants for property developers encourage modular home construction in Canada. In Build Offsite.

7 Hixson, R. (17 Nov 2023). B.C. begins project to create standardized home designs. In Site News.

8 Murray, C. (2024). The great housing hijack. Allen & Unwin, Sydney, p.99.

9 De Graff, R. (7 May 2015). The same architecture that once embodied social mobility now helps to prevent it. In Deezen.

10 De Graaf, R. (24 April 2015). Architecture is now a tool of capital, complicit in a purpose antithetical to its social mission. In The Architectural Review.

11 Peters, S., Pinkse, J. & Winch, G. (2023). Driving change in UK housing construction: a Sisyphean task? In Productivity Insights, no. 17, The Productivity Institute.

12 Peters, S., Pinkse, J. & Winch, G. (2023). Driving change in UK housing construction: a Sisyphean task? In Productivity Insights, no. 17, The Productivity Institute, p.16.

13 Peters, S., Pinkse, J. & Winch, G. (2023). Driving change in UK housing construction: a Sisyphean task? In Productivity Insights, no. 17, The Productivity Institute, p.16.

14 Peters, S., Pinkse, J. & Winch, G. (2023). Driving change in UK housing construction: a Sisyphean task? In Productivity Insights, no. 17, The Productivity Institute, p.14.