Few topics in the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry are more polarising than modular construction. On the one hand, those for modular construction will talk at you at length about the need to modernise or die. McKinsey & Company reports are cited. Analogies with the automotive industry are made. And channelling their inner Henry Ford, standardise, standardise, standardise goes the beat of the drum. Architects are considered superfluous and an unnecessary nuisance and expense. Mass production is the answer. Give us volume, and we’ll fix the AEC industry. And on the way, we’ll solve the housing crisis. Standardisation + Volume = Progress.

On the other hand, those against modular construction dismiss it as a cookie-cutter path to mediocrity. Soleless, sterile and generic. Cheap and flimsy. A solution to the wrong problem. Contractual and professional liability constraints are cited. The belief that every project is different is upheld like an axiomatic, self-evident, and utterly indisputable fact. That architecture cannot, and should not, be the same as manufacturing. Reinstate professional fee scales and prohibit Design and Construct procurement.

And if that wasn’t polarising enough, then there are the bean counters, who, without any AEC experience, use modular construction to further their own political and financial interests – solving the housing crisis one spreadsheet at a time. Finally, there are the tech evangelists claiming that “AI and other tech” will solve all of construction’s issues – but offer no insight as to how.

Truth be told, all of the above perspectives and biases have some element of truth to them. But before reconciling such divergent thoughts and moving beyond the shitty first draft, we need to understand how we got to this point and bust some of the myths holding us back.

What is modular construction?

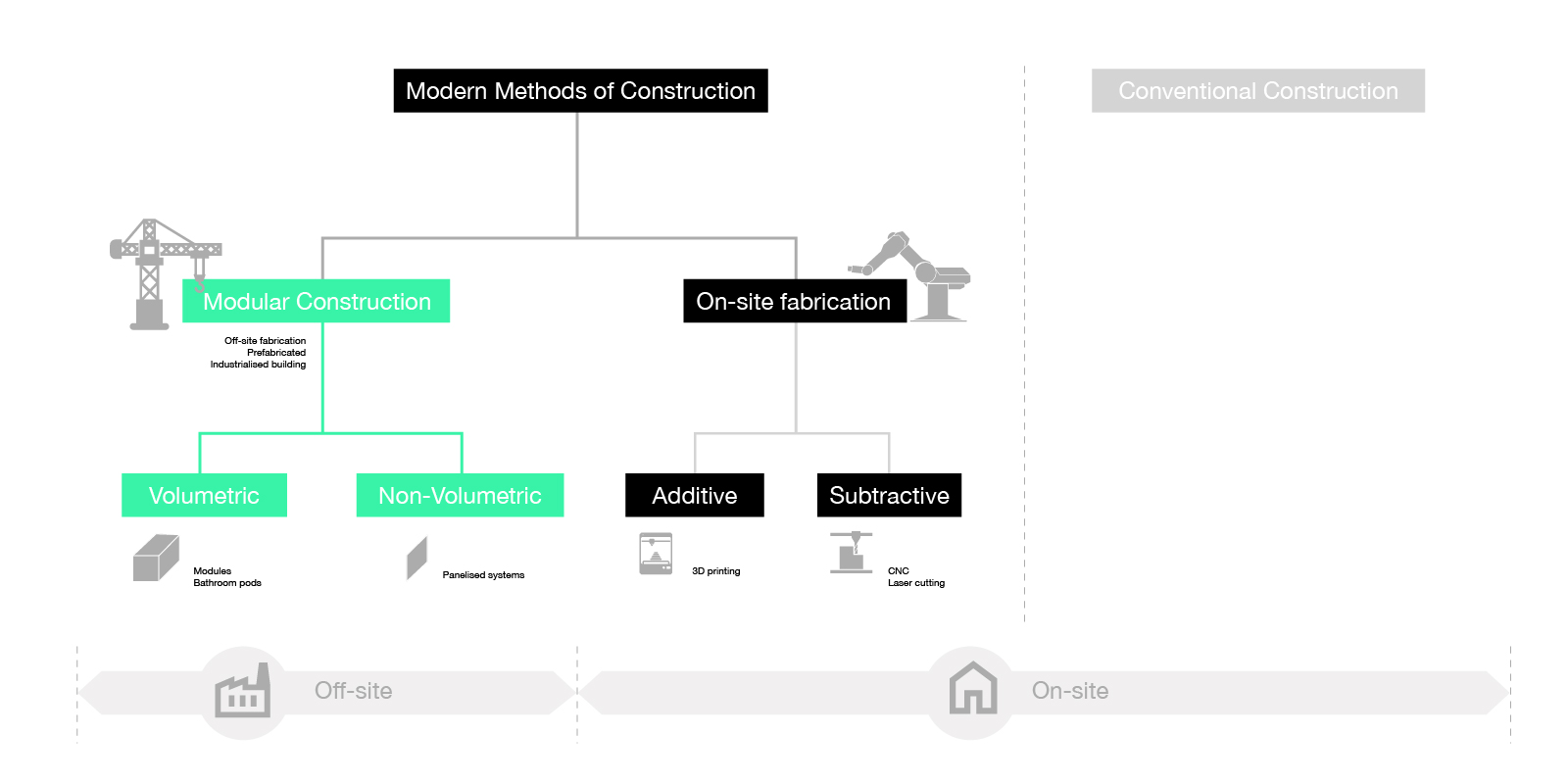

Modular construction generally refers to building elements prefabricated off-site and then installed on-site. However, terms such as Prefab, Prefabrication, Off-site and Industrialised Construction are used interchangeably to describe modular construction in different countries. The key point here is not the nomenclature but the fundamentally different philosophy from construction.

Whereas Conventional construction uses raw materials in situ, modular construction embraces off-site prefabrication in a factory. In other words, it represents a shift away from construction towards manufacturing. Modular construction falls under the umbrella term Modern Methods of Construction, which acknowledges that fabrication can occur both off-site and on-site, as is the case with 3D printing and other processes.

Types of Modular Construction

Under modular construction are two subcategories – volumetric and non-volumetric.

Volumetric modular construction involves the off-site prefabrication of individual modules connected on-site. For example, a volumetric module may be an apartment, hotel room, or something smaller, such as a bathroom ‘pod’. The maximum size of the module is often dictated by the dimensional limitations of trucking, as special permits or delivery protocols are required beyond a certain size. The main benefit of volumetric modular construction is that a greater amount of assembly can take place in the controlled environment of the factory. Conversely, this is also its biggest weakness, as significant transportation costs are due to “shipping air”.

Non-volumetric modular construction involves the off-site prefabrication of individual building elements connected on-site. Common examples of non-volumetric modular building elements include beams, columns, sections of building façade, wall panels, and floor cassettes. The main benefit of non-volumetric modular construction is that elements can be ‘flat’ packed, reducing transportation costs. The downside of this is a greater reliance on on-site assembly.

It is important to note that modular construction and conventional construction exist along a spectrum. A conventional construction project may contain modular elements, and a modular construction project may still require some elements to be constructed on-site. Therefore, the definition of what constitutes a modular building is somewhat blurred but relates more to the extent of off-site prefabrication used. In other words, modular construction is a relative value, not an absolute.

The promise of modular

Prefabrication in housing and construction has been around since the nineteenth century. Some have focused on utilitarian prefabrication, such as the old demountable classrooms found across Australian schools. Introduced in the 1960s, these were designed to last ten years. Half a century on, approximately 6,000 of them are still in use.

Others, such as Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion (1927) and Matti Suuronen’s Futuro (1968), focused on aesthetic or formal reasoning, also known by some as conceptual prefabrication.1

Either way, the core promise of modular construction is that it is quicker, cheaper, and higher quality. More recently, it has also been promoted as having lower embodied carbon, the saviour to the industry’s ageing labour markets, and some even go as far as to claim it is the only plausible solution to solving the housing crisis. Sounds great, so what’s the problem?

Quicker, cheaper and better?

To begin with, a lot of the claims are unfounded marketing hyperbole. Take, for example, the claim that modular construction saves 45% carbon compared to traditional construction methods.2 No less than ten websites published the claim,3 all of them referencing a press release related to the findings from the report, ‘Life Cycle Assessments of The Valentine, Gants Hill, UK and George Street, Croydon, UK’, commissioned by Tide Construction and Vision Modular Systems.4 The problem is that the report is not publicly available for commercial reasons. Despite this lack of transparency, Tide Construction’s chief executive Christy Hayes claims the research “clearly and credibly” demonstrates to the industry the embodied carbon savings that can be achieved through modular.5 Marketing fodder we are just meant to eat up without question.

But beyond this, there is mounting evidence that modular’s core promise of being quicker, cheaper, and higher quality is either completely unfounded or, to take a more optimistic perspective, needs to be better executed by many organisations.

Modular construction is failing…

In June this year, the UK volumetric modular builder Ilke Homes fell into administration. Despite claiming a 4,200-home pipeline, they accumulated over £107m in losses in just four years.6 According to the administrator, the cause of its failure: “The market and economic headwinds have proven too strong to overcome”.7 But it was just the latest causality in a long line of modular construction failures.

Just a month earlier, Legal and General (L&G) Modular Homes in the UK closed up shop after racking up £174m in losses over seven years.8 In a statement, L&G stated, “A number of factors, including long planning delays and the impact of recent macro events such as Covid, have meant the business has not been able to secure the necessary scale of pipeline to make the current model work.”9 Only two months before L&G’s announcement, it was revealed that its Selby and Bristol developments were heavily contaminated with black mould due to the factory-built volumetric homes stored ahead of installation on site.10 The Bristol project also contained faulty foundations, requiring homes to be removed while foundations were rectified, causing an additional 12-month delay.11

…again and again…

In May last year, UK-based House by Urban Splash collapsed with more than £20m in debts. Administrators cited “the under-performance of its modular facility, which has been loss-making for a prolonged period” as the cause of the failure. The administrator for House by Urban Splash claimed that the underperformance of the volumetric factory was due to “a number of factors, including design issues resulting in production defects and re-working the modular units.”12

In March last year, UK-based volumetric builder Caledonian Modular went into administration, racking up more than £20m of losses in just 18 months.13 JRL Group later purchased the company for just £6.25m. The cause of the collapse was cited as rising raw materials and staff costs.14

| Ilke Homes | Urban Splash | L&G Modular | Caledonian Modular | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | Profit | Revenue | Profit | Revenue | Profit | Revenue | Profit | |

| 2022 | £27.5m | (£41.2m) | – | – | – | – | £32.7m | (£10.7m) |

| 2021 | £12.7m | (£34m) | – | – | £12.2m | (£36.8m) | £64.5m | (£11.2m) |

| 2020 | £3m | (£23m) | £4.7m | (£3.7m) | – | (£29.1m) | £45.3m | (£2.8m) |

| 2019 | £0.26m | (£7.7m) | £30.5m | (£3.4m) | – | (£31m) | £50m | (£0.7m) |

| 2018 | – | – | – | – | – | (£21m) | £52.8m | (£3.7m) |

| 2017 | – | – | – | – | – | (£46m) | £22.7m | – |

| 2016 | – | – | – | – | – | (£9m) | – | – |

Ironically, both L&G Modular and House by Urban Splash were presented as exemplar case studies in the 2016 report Modernise or die, the UK construction labour model review.15 But even those who haven’t failed are struggling.

Even those who haven’t failed are struggling

The largest UK modular home builder, TopHat, has yet to make a profit but insists it will be profitable in the next three years.16 Its pre-tax loss for the year ending October 31, 2022, stood at £20.4 million, and this was despite production doubling.17 And the much-hailed Swedish modular builder BoKlok (‘Live Wise’ in Swedish), a joint venture between Skanska and Ikea, announced that their first UK project, BoKlok on the Brook in Bristol, was running 12 months over schedule. A spokesperson of BoKlok cited “a number of unforeseen issues on site as well as the ongoing challenges with regard to supply chain, materials and labour across the whole industry.”18 And only three months ago, BoKlok made mass layoffs in their Gullringen factory due to weak housing demand.19

…and it’s happening everywhere

Make no mistake: the troubles facing modular aren’t confined to the UK. In Australia, Lendlease’s DesignMake, which focused on prefabricated mass timber, shut down in June 2019, less than four years after it began.20 This was despite operating pre-COVID-19 pandemic and winning numerous design awards.

In the USA, Katerra burned through US$3 billion in funding in just five years only to implode into supernova stardust. Katerra blamed its downfall on “soaring labour and construction costs” as reasons for its financial difficulties.21

461 Dean St, New York, by SHoP Architects, became the tallest modular building in the world at 32-storyes but ran two years over schedule and tens of millions of dollars over budget.22 The delays were attributed to “the inability of the factory to produce modules as quickly as required to keep up with the crane on-site.” Additionally, some modules had to be gutted and renovated on-site because of water damage due to “leaks caused by improper detailing of the temporary roof membrane on the lower level modules.”23

More recently, US-based Entekra shut down operations after six years as they “struggled to maintain profitability, despite having secured several large contracts.”24

History repeats

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

George Santayana

One may be forgiven for thinking that modular’s problems are a recent phenomenon. It is not. As Mathew Aitchison explains, “The problems and failures of the past have not been fully understood and continue to provide a barrier to the future of industrialised housing ventures.”25 He continues, asking, “Why does the industry, its researchers, developers and its supporters continue to make the same – in some cases, exactly the same – mistakes of the 1950s?”26 The answer lies in modular construction’s misplaced reverence in the automotive industry and its mass production history.

The legacies of Frederick Taylor & Henry Ford

Two important historical paradigms emerged as a result of the Industrial Revolution – Taylorism and Fordism. Taylorism arose as the scientific management of rationalised industrial work tasks into discrete, measurable, simpler, segmented components. Scientific management, Taylor wrote, consists of “knowing exactly what you want men to do and then see that they do it in the best and cheapest way.”27

This was coupled with Henry Ford’s appropriation of the assembly line from the food industry towards a new application of routinised and standardised production of the Model T car from 1909 onwards. Fordism, as it came to be known, is the manufacturing process designed to produce standardised, low-cost goods for mass consumption. Via Taylorism and Fordism, repetitive production, routinisation and standardisation took command.28

The Henry Ford syndrome

For someone looking to improve construction, the premise was simple: “Why can’t we mass-produce houses – standard, well-designed, at low-cost – in the same way Ford mass-produced cars?” But this line of thinking, coined the Henry Ford Syndrome by Gilbert Herbert, has been central to modular’s repeated failure.29 Case in point, The General Panel Corporation.

Post World War II, Modernist architects Konrad Washsmann and Walter Gropius established the General Panel Corporation in the USA. Their Packaged House product had a market, a highly talented team, a stream of finance, and government backing. Yet it failed:

…the advocates of the factory-built house turned again and again to the paradigm of the automobile for encouragement and for justification. But this analogy was a false one. Car prices were initially high, to cover high tooling costs and disproportionate overheads, while production slowly increased. But as a generic product, the car was unique, and its manufacturers had a complete monopoly; one either paid a high price or did not acquire a car… But industrialised housing did not produce unique products, the competition of the traditionally built house was an ever-present factor, and the industry was denied that sheltered growth period it needed to reach the critical level of mass production.

Gilbert Herbert30

Given recent events, one could be forgiven for thinking the quote was written just yesterday. But the passage was written in 1984 about a company that failed in 1952. It is clear that some 70 years on, the industry is still repeating the mistakes and fallacies of the past.

History is bunk

You all remember, I suppose, that beautiful and inspired saying of Our Ford’s: History is bunk.

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

The misplaced reverence of Fordism reads like a dystopian novel. In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, the futuristic World State is built upon the principles of Henry Ford’s assembly line: mass production, homogeneity, predictability, and consumption of disposable consumer goods. Citizens are environmentally engineered via the Bokanovsky’s Process, producing ninety-six identical humans from a single embryo. Children are indoctrinated by hypnopaedia from birth, and the Bureau of Propaganda controls the media. As the creator of their society, the deity-like figure of Henry Ford, known as Our Ford, replaces religion altogether. And all that came before is forgotten in the name of progress.

Dystopian societies aside, the parallels with ignoring history are deeply problematic. Henry Ford once said, “History is more or less bunk. It is tradition. We don’t want tradition. We want to live in the present and the only history that is worth a tinker’s dam is the history we make today.”32 While this mindset might be a prerequisite for disruptive innovation, it comes at a significant cost, as many modular organisations have discovered. Insanity, after all, as Albert Einstein noted, is doing the same thing over and over again but expecting different results. Modular construction can be successful, but it needs to be done differently and without the rose-tinted Ford glasses.

Conclusion

To succeed in industrialised construction, we must shake off the Henry Ford Syndrome and realise that it requires its own solution. And this begins with questioning the belief that Mass Standardisation + Mass Production is the only way forward. In our next article, we’ll explore how this can occur by reframing certain core assumptions.

References

1 Aitchison, M. (2018). Prefab housing and the future of building: Product to process. Lund Humphries, London, p.43.

2 Lowe, T. (6 Jun 2022). Modular construction emits 45% less carbon than traditional methods, report finds. In Building magazine.

3 Building magazine, BD online, Archinect, Housing today, Unlock net zero, Future build, Grand designs, Inside Housing, Construction enquirer, and the RIBA journal.

4 The research was carried out by Dr Tim Forman, Senior Research Associate at University of Cambridge, Professor Francesco Pomponi and Dr Ruth Saint of Edinburgh Napier University.

5 Cousins, S. (13 Jun 2022). Modular schemes slash embodied carbon by over 40%, research shows. In RIBA Journal.

6 Morby, A. (6 Jan 2022). Ilke Homes losses over four years top £100m. In Construction enquirer.

7 Morby, A. (30 Jun 2023). Ilke Homes falls into administration. In Construction enquirer.

8 Morby, A. (3 Oct 2022). L&G modular homes amassed loss deepens to £174m. In Construction enquirer.

9 Prior, G. (4 May 2023). L&G halts production at modular homes factory. In Construction enquirer.

10 Prior, G. (9 Mar 2023). L&G modular homes hit by mould problems. In Construction enquirer.

11 Knott, J. (28 Jul 2023). L&G dismantles Bristol modular homes due to foundation problems. In Construction News.

12 Ing, W. (14 Jul 2022). House by Urban Splash’s factory problems laid bare. In Architects’ journal.

13 Pitcher, G. (28 Apr 2022). Caledonian Modular’s losses and debts revealed. In Construction news.

14 Gerrard, N. (17 Mar 2022). Rising costs blamed for Caledonian Modular administration. In Construction management.

15 Farmer, M. (2016). Modernise or die: The Farmer review of the UK construction labour model.

16 The construction index. (8 Aug 2023). Volumetric builder still three years away from making a profit. In The construction index.

17 Build offsite. (11 Aug 2023). Diverse trajectories of modular house builders and finance partners in the UK. In Build offsite.

18 Humphries, W. (6 Jan 2023). Dream of Ikea home falls apart for buyers facing costly delays. In The Times.

19 Lesprom. (16 Jun 2023). Swedish Boklok announces layoffs amidst challenging housing market. In Lesprom.

20 Perinotto, T. (11 Jun 2019). Future of Lendlease’s DesignMake is under review. In The fifth estate.

21 Weinberg, C. (1 Jun 2021). SoftBank-backed Katerra to shut down. In The information.

22 Stinson, L. (23 Nov 2016). The world’s tallest modular building may teach cities to build cheaper housing. In Wired.

23 The American Institute of Architects (2019). Design for modular construction: An introduction for architects. p.22.

24 Fleisher, G. (5 July 2023). What to make of Entekra’s Fall? In Offsite builder.

25 Aitchison, M. (2018). Prefab housing and the future of building: Product to process. Lund Humphries, London, p.17.

26 Aitchison, M. (2018). Prefab housing and the future of building: Product to process. Lund Humphries, London, p.20.

27 Taylor, F. (1911). The principles of scientific management. Harper Brothers, London.

28 Gartman, D. (2009) From autos to architecture: Fordism and architectural aesthetics in the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press, New York, pp.7-11.

29 Herbert, G. (1984). The Dream of the Factory Made House. MIT Press, Cambridge, p.3.

30 Herbert, G. (1984). The Dream of the Factory Made House. MIT Press, Cambridge, p.3.

31 Gropius, W. & Wachsmann, K. (2021). The General Panel Corporation. In The Dream of the Factory-Made House. MIT Press, Cambridge.

32 Wheeler, C. (26 May 1916). In Chicago Tribune.

11 Comments

ignasiperezarnal

Dear Paul,

I have to congratulate you for this article. We are going to launch a 3D Wooden Modules factory in Spain and we are observing the market very carefully. And we agree you in your analysis.

But anyway, I do think that the examples you are analysing are UK and USA based, while in China, Japan, also in Austria and The Netherlands areincubating very interesting and important examples. Some of them are making in one year more than all the US and UK production nad this is also important to point out.

Check Kauffmann, Gropyus, Sekisui, Broad, Toyota… and I believe you will agree me on that.

Eager to check your new next article, where you will explore how this can occur by reframing certain core assumptions. AI, Lean Construction; Building Operating Systems… have to help us on that.

Inviting you to be one of our analysts in our Board of Constant Innovation, congrats again for giving us some light in this dark side for architects and builders…

Ignasi Pérez Arnal

Launching the next future through -we hope- one of the biggest pre-seed phase for begining to change our AECO sector

Paul Wintour

Hi Ignasi

Thanks for your feedback. With the examples you point out, just a few observations.

– Investors have invested over 250M euros in Gropyus. They have completed only a single building. And I believe it isn’t even sold; it is just a proof-of-concept/ display home. Raising vast sums of external capital doesn’t make a company successful. Maybe they will succeed, but it is far too early to know.

– Sekisui House build about 50,000 houses a year. They have also been around for 60 years, gradually improving and automating. Currently, they are adopting a mass customisation strategy. Their houses are also marketed as high quality with a price premium. This is a very different value proposition to most modular organisations.

Shabbir Lokhandwala

Dear Paul,

Not all Precast / Modular Construction based companies / projects are failing. The reasons for some of the companies who have failed as listed by you are many :

– They were trying to explore on multiple fronts at the same time like developing software for construction tech at the same time adopting modular construction tech

– Burning chunk of money on several fronts ; like Marketing, Marketing, Marketing ; which might not be always required for a brick and mortar business

There are Countries like, Singapore, Malaysia, India as well; using Modular, Precast for high rise buildings as per the needs of the project delivery timely projects.

Sometimes delivering projects on time = Savings on the Projects = Profits $$$ for the End Clients

There are numerous examples which have worked out well.

Few companies have gone down because of Cash flow and mis management of money in the construction business.

Also I agree that modular construction / precast buildings are not fit to be made at all locations / projects. Where so ever this technology brings value to the client OR Overall Project; it shall be used.

Great Example is Kuwait International Airport; One of the key largest project going on in the world right now ; wherein precast / modular components are used in Facade, Main structure etc; to achieve the component designs using technology; again we have been a part of its design.

Well your article is good to understand how companies have failed in precast / modular business but there are positive and successful case studies as well.

Paul Wintour

I think attributing the failure of companies who have lost hundreds of millions of dollars on excessive marketing is absurd. They also weren’t exploring multiple fronts at all. This is a very simplitic critique which fails to address the real issues at play.

Emanuel Resendes

Hi Paul.

Thanks for the article. As a significant volumetric modular builder in Canada, I appreciate your explanation of volumetric and non-volumetric modular and the many references provided to tap into.

I see the need to create a database that goes into depth into what works and what doesn’t work to avoid repeating the mistakes in the past.

I look forward to reading your follow-up article.

Paul Wintour

Thanks Emanuel. Glad you found it helpful.

Yes, I think part of the problem is that, as an industry, there is insufficient critical thought and sharing of lessons learnt. Party this is attributed to organisations thinking they have some unique IP and not wanting to give anything away. Partly, it is because they are funded by VC firms who want them to operate in stealth mode, and everyone is under NDAs. I don’t know the solution, but if there is no collective learning happening, we will see many of the same mistakes repeated repeatedly.

Maxime Brard

Thanks paul,

This is probably the most interesting article I’ve read on off-site construction and the reasons of some failures.

Thank you for this well-documented work on Anglo-Saxon modular construction.

Paul Wintour

You’re welcome Maxime. Glad you enjoyed it.

Andrew

Interesting article, and to the point. With reference the Boklok homes, please clarify who was the manufacture of this product. As it is my understanding that these were manufactured in the Baltics.

Paul Wintour

The main Boklok factory is in Sweden. But for the UK, they signed a 5-year contract back in 2020 with TopHat. TopHat’s factory is in Derby, UK.

https://tophat.io/news-views/boklok-uk-appoints-modular-housing-manufacturer-tophat-to-deliver-first-uk-homes/

Diego Kapaz

Helo, Paul.

Wonderful article, like many others in this blog.

I would like to contribute suggesting to look on brazilian architect Lelé’s work.

With a life time of research and successfull buildings and constuiction systems based on modularity, without necessarily repetitiveness, he managed to delve into practice on several issues brougth here in the article and comments, allways without loosing both beautyness and funcionality.