For many Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) organisations, developing a design technology strategy involves determining the number of Autodesk AEC Collection subscriptions required and allocating the corresponding budget. Mix in a bit of Generative AI, and job done. However, this simplified approach overlooks the longer-term forces shaping the future of work. This isn’t about grandiose statements that the future is AI. It is about understanding the profound technical forces already in play. So, what are these forces, and how will they impact the way AEC organisations do things?

The future of BIM

Most AEC organisations have explored generative AI to some extent, as evidenced by the AI slop proliferating on social media. But when it comes to the future of design technology, often coined BIM 2.0, most discourse centres on two topics: the cloud and (open) data. The AEC Magazine, for example, defines BIM 2.0 as cloud-based BIM with better data and fabrication capabilities.1 Similarly, the Future AEC Software Specification, published by several architects, serves as a wish list for an ecosystem of modular applications with a unifying data framework.2 Other contributors, such as Greg Schleusner from HOK, have presented their view of how AEC data should work. What all of these approaches touch on, but are not entirely made explicit, is the underlying technical forces already in motion that must be present to enable this desired future state.

The inevitable technological forces

To better explain these technical forces at play, this article references the work of Kevin Kelly, technologist and founding executive editor of Wired magazine. His book, The Inevitable, suggests that much of what will happen in the next thirty years is inevitable, driven by technological trends already in motion. Kelly lists twelve technological forces shaping our future: Becoming, cognifying, flowing, screening, accessing, sharing, filtering, remixing, interacting, tracking, questioning, and beginning.

Some of these forces are more relevant to the AEC than others, and many overlap. As such, this article has taken the liberty of condensing the list down to six technological forces most affecting the AEC industry: Becoming, cognifying, flowing, screening, accessing and remixing. While these should be seen as trajectories, not destinies, they help illuminate where AEC design technology is headed and challenge many long-held assumptions. The hope is that by illuminating these forces, AEC organisations can better prepare for their future.

#1 Becoming

Everything, without exception, requires additional energy and order to maintain itself. In the initial age of computing, it was common to hold off on upgrading. Much like painting an internal wall only to realise that the adjacent wall also should be painted, the task never seemed to end. Each upgrade seemed to trigger other upgrades. And so many avoided it for as long as possible, and only then did they do so begrudgingly. Even today, many AEC organisations deploy new Revit versions only every two or three years to minimise disruption.

But delaying upgrading is often more destructive. Minor upgrades tend to back up until, eventually, the big upgrade reaches problematic proportions. Consider a recent BBC article that highlighted how bad this can become.4 Deutsche Bahn, the German railway service, runs on Windows 3.11 and MS-DOS systems released 32 and 44 years ago, respectively. Meanwhile, the trains in San Francisco’s Muni Metro light railway won’t start up in the morning until someone sticks a floppy disk into the computer that loads DOS software on the railway’s Automatic Train Control System. Deferred maintenance, as it is known, allows reliance on older technology to accumulate over time until, eventually, users are trapped.

However, with the rise of Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), software updates are becoming increasingly frequent. This technological force is far more significant than merely a technical inconvenience. Indeed, with much of today’s web-based software, the upgrade process occurs automatically in the background, with minimal to no impact on the end user. Instead, this trajectory symbolises that “all of us – every one of us – will be endless newbies in the future simply trying to keep up.”5 Kelly terms this constant state of becoming Protopia. And, importantly, Protopia will generate almost as many new problems as it will new benefits.6

Becoming in the AEC industry

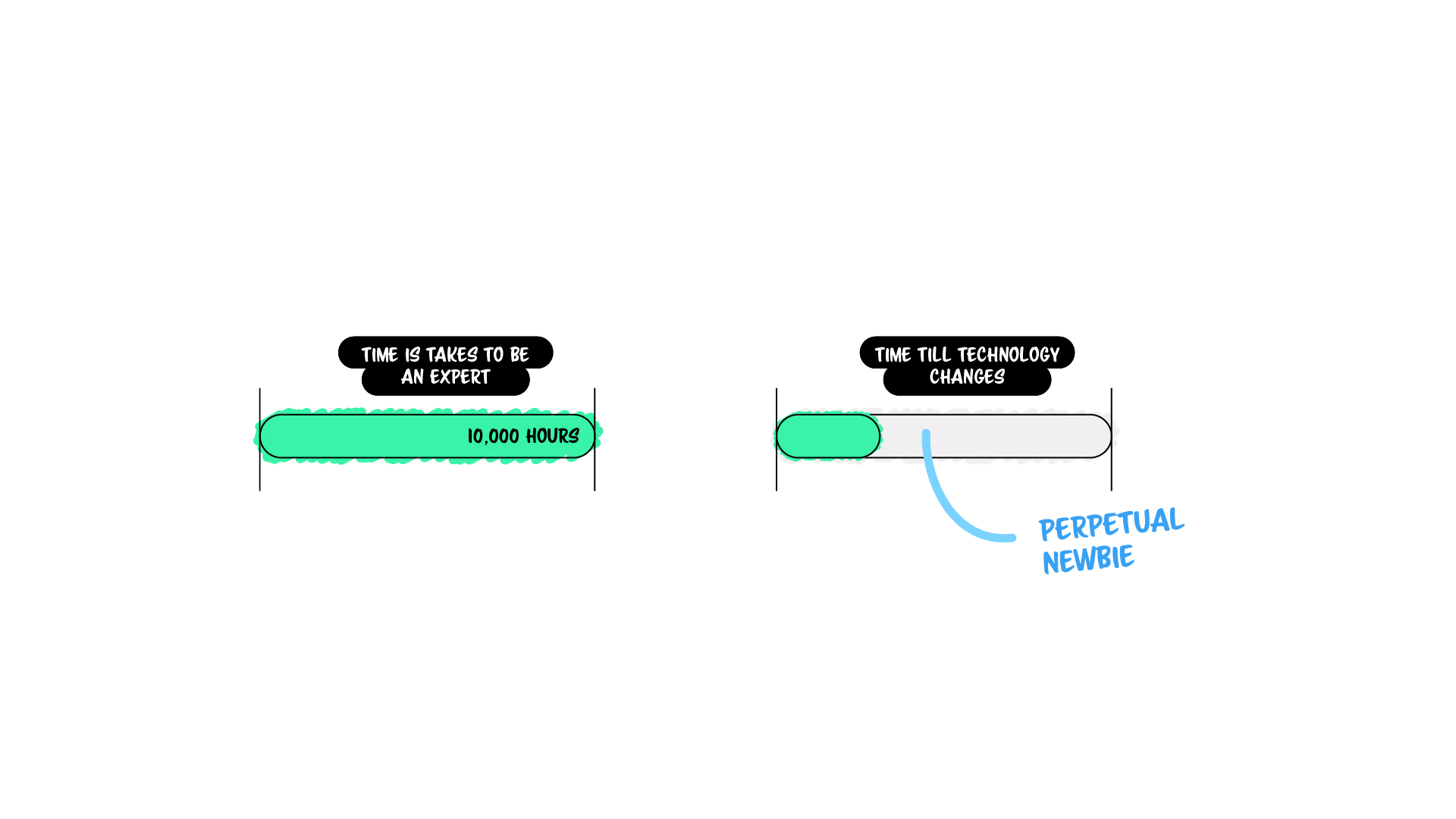

Consider the following. Research by neurologist Daniel Levitin and popularised by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers, states that “10,000 hours of practice is required to achieve the level of mastery associated with being a world-class expert – in anything.”7 This is known as the 10,000-hour rule and can be seen across many professions. Ten thousand hours is approximately five years of full-time work. If technological change accelerates faster than that limit, we simply won’t have sufficient time to master the technology before it becomes displaced.

Granted, not every AEC organisation needs world-class experts, but this technological force fundamentally changes how we view expertise. Many organisations search for that one perfect job candidate who is already an expert in their field – no training needed. Simply hit the ground and run. But in a world where software expertise has a shelf life of years, if not months, fostering a culture of learning will be more important than hiring an expert. In other words, we need to get comfortable being uncomfortable.

#2 Cognifying

The human race has undergone three industrial revolutions—steam, electricity, and digital—and we are currently in the fourth, which is Artificial Intelligence/Internet of Things. Cognifying is the process of embedding smartness or intelligence into inert objects and, according to Kelly, will be “hundreds of times more disruptive to our lives than the transformations gained by industrialisation.”8 As our relationship with machines evolves, there will be the predictable cycle of denial again and again. Kelly terms these the Seven stages of robot replacement9:

While technology is often framed as being subservient to human thinking, the reality is, “Our most important mechanical inventions are not machines that do what humans do better, but machines that can do things we can’t do at all.”10 This is not a race against machines. If we race against them, we lose. This is a race with the machines.

Cognifying in the AEC industry

For many professionals, the idea that their jobs can be automated seems preposterous. Architecture or engineering is far too complex to be automated. And it’s true. If professions are considered some amorphous, all-encompassing black-box, then yes, it will take some time for technology to replace professionals.

However, if we are honest with ourselves and take a deep look at what professionals do, it’s clear that much of what professionals do can be broken down into discrete tasks that can be either partially or fully automated. And we’re already witnessing this. Emails and documents can be summarised, and visualisations and software code can be generated with simple text prompts. And we’re only getting started.

More and more tasks will eventually be automated. As this expansion takes place, we will be forced to re-evaluate what it means to be a professional. This has less to do with technical unemployment and more to do with the eventual dismantling of the traditional professions.

#3 Flowing

The first version of a new medium imitates the medium it replaces. As such, the initial digital age borrowed from the industrial age. Steve Jobs, for example, was an early proponent of Skeuomorphism, the design concept where digital objects mimic real-world counterparts. Think the Apple Macintosh’s trash can, iBooks’ leather cover, or Notes’ yellow legal pad look. Our computer screens displayed a desktop, folders, and files—digital objects that mimicked physical objects.

Moreover, these digital objects were hierarchically ordered. As Mario Carpo writes, from the beginning of time, humankind has conceived and honed classification as a way to find some order in the world as well as the basic requirement of knowing where something is when we need it.11 Taxonomies are as old as Western philosophy. Consider Aristotle, who divided all names into ten categories known as Praedicamenta.12 Taken as a whole, these visual cues and organising principles of the initial digital age aimed to make the new digital environment familiar and comfortable.

Second digital age

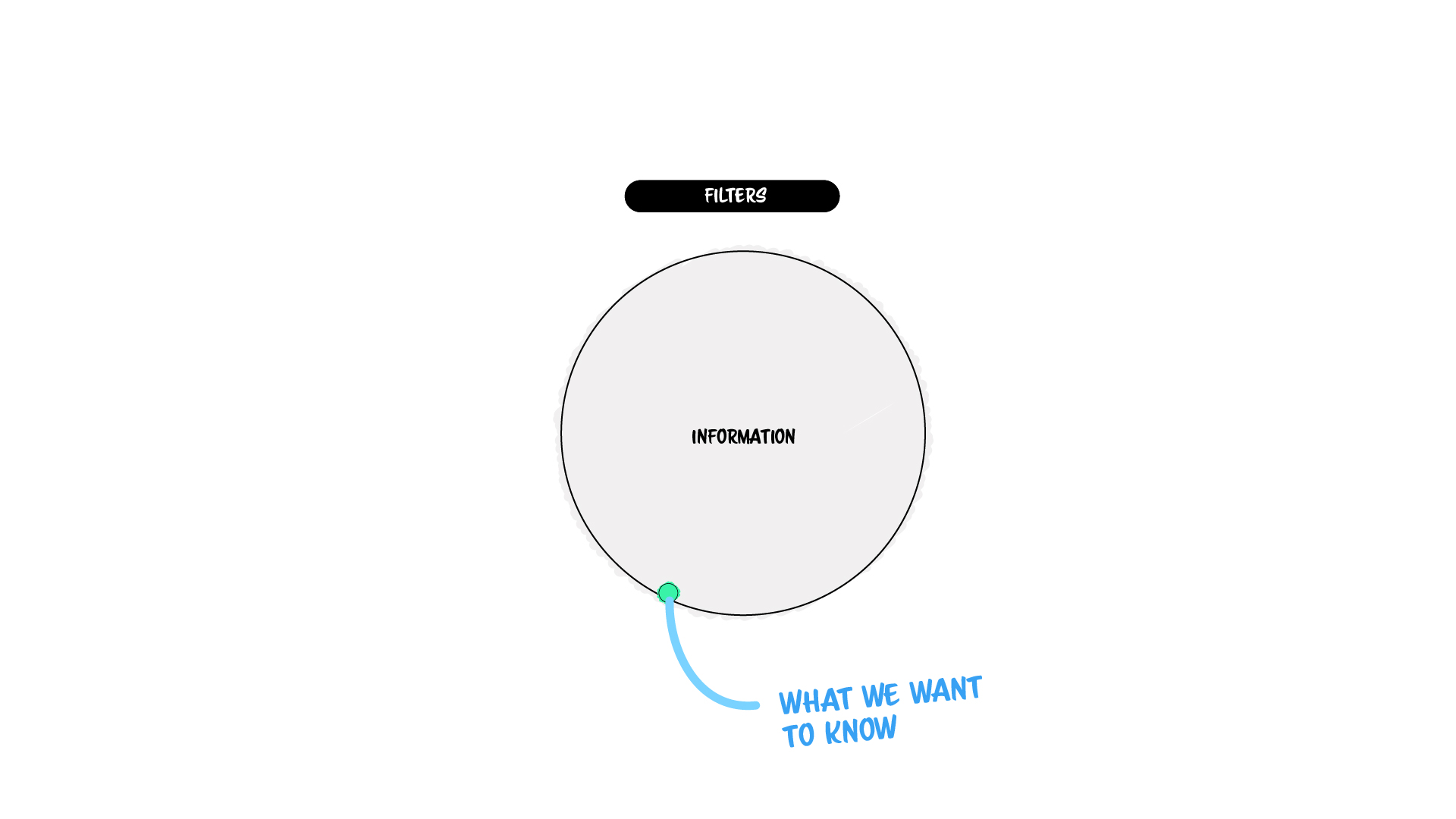

The second digital age overturned the office metaphor and brought us the organising principles of the web. Pages were not organised into folders but arranged into a networked web. Information became networked, linked together through hyperlinks. This pivotal change was far more significant than merely a different way of finding the same information. It fundamentally shaped how we understand knowledge – from one that is curated and fixed to one that is distributed and dynamic. Instead of relying on categorisation to order and find information, the web introduced the concept of searching and filtering. Google’s original tagline, for example, was “Search don’t sort”. As David Weinberger explains in his book Too big to know, “Filters no longer filter out. They filter forward, bringing their results to the front. What doesn’t make it through a filter is still visible and available in the background.”13

Third digital age

We are now transitioning into the third age of computing, where the prime unit is flows and streams in real-time. Consider Facebook and Twitter feeds, Uber surge pricing, streaming music on Spotify, or movies on Netflix. Again, this shift is far more profound than merely a different way of finding the same information. Firstly, it alters our perception of ownership, a topic we’ll address shortly. Secondly, to operate in real-time, everything must flow. In other words, our technological infrastructure needs to liquefy.

Flowing in the AEC industry

If we consider flowing in the context of digital technology, the AEC industry is still disturbingly very much in the first digital age. We are inundated with hierarchical classification systems, such as Uniclass (UK), OmniClass (USA), and Natspec’s National Classification System (Australia). We speak of Common Data Environments (CDE) and the need for a central repository to find the single source of truth. However, despite the ability to have ‘live’ external links, this is avoided for quality assurance and contractual purposes. Instead, the latest BIM models and accompanying transmittal are uploaded every week for consumption by the rest of the project team. Only the necessary information is included, with all extraneous information purged from existence.

Despite the above, there are several areas where we can see the adoption of the second digital age. Many organisations, for example, have adopted information management software, where search is the dominant discovery method. Product libraries are a thing of the past, surpassed by online technical data sheets and standards. Additionally, intranets and team workspaces are enabling co-authorship and the integration of external knowledge sources rather than relying on static PDF documents.

Embrace the third age of computing

Beginning with Flux around 2015, the industry has started to embrace the third age of computing, talking of “transferring data, not files”. Since then, we have seen the rise of Speckle streams for real-time exchange of model data. Integrations with open databases, such as EPiC, ICE and EC3, are being utilised for Life Cycle Analyses (LCA). Further abreast, the GIS industry has long since streamed data, such as cadastre and planning legislation, in real-time. Each GIS dataset contains detailed information about the custodian, when and how the data was captured, and its accuracy level. In other words, data is allowed to flow, but most importantly, we are supplied with supporting information so that we can trust it. The value proposition here is convenience – the convenience of accessing information simply and easily. As the AEC industry embraces flows and streams, we will see a shift towards dematerialisation and decentralisation.

#4 Screening

Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press, invented in 1450, enabled knowledge to be captured and recorded in books. The invention represented a significant improvement over orally transmitted information and manually scribed documents, as it allowed information to be disseminated far more easily. But Gutenberg’s invention did something else; it fundamentally shaped our perception of knowledge and how it should be captured.

As Kelly describes, the mass-produced books changed the way people thought and “instilled in society a reverence for precision, an appreciation for linear logic, a passion for objectivity and an allegiance to authority, whose truth was as fixed and final as a book.”14 But we’ve come to realise that ideas are often intertwined and related. This is why Kelly argues that “what those kinds of books have always wanted was to be annotated, marked up, underlined, bookmarked, summarised, cross-referenced, hyperlinked, shared, and talked to.”15 And this is what being digital allows them to do.

Screening includes reading words, as well as viewing images, watching videos, and listening to sound or music. In other words, it is the non-linear method of absorbing digital information. Screening, according to Kelly, will encourage rapid pattern-making by associating one idea with another. Wikipedia, for example, networks ideas together via hyperlinks, enabling readers to go down a digital rabbit hole. Or consider products such as Apple TV, which aggregates various media streams, including Netflix, ABC, and Disney+, into a single platform.

Screening in the AEC industry

Taken as a whole, AEC data is highly fragmented and disconnected. Despite AEC’s desire for a Common Data Environment, output remains very much siloed. Remove the 300-page InDesign booklet, and much of the logic and decision-making process becomes obscure. Environmental analysis models are often kept separate from the main design model, thereby limiting any feedback loop. The output of any computational design automation is baked into the design model, severing the underlying logic that generated the elements. Metadata in the BIM model is often static and disconnected from any external source. What is to be built in the form of a BIM model is separated from how it must perform, which is captured in the specification. Redline markups are applied to a PDF independently of where the model was created.

But there are glimmers of hope. Numerous start-ups are starting to connect pieces that have historically been disconnected. Speckle, as we’ve previously seen, enables real-time model data exchange between multiple authoring software, while also allowing changes to be tracked in real-time. Arcol enables comments to be made directly within the project, keeping discussions within the context in which they’re made. Motif, a new start-up formed by former Autodesk executives, has an infinite canvas to capture ideas that can then be showcased via a web app. Canoa enables the creation of mood boards and furniture arrangements using live catalogue data from suppliers. UpCodes connects building codes with authoring software to help create a compliant solution.

Much of the functionality described above is common among new start-ups and represents an overwhelming trend to connect information in meaningful ways. As more data begins to flow and is allowed to connect, screening will enable us to explore the complete picture, not just a snapshot of it.

#5 Accessing

Back in 2025, TechCruch noted:

Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.16

Put simply, possession is not as important as it once was. But access is more important than ever. As digital technology accelerates dematerialisation, we’ll see a steady migration from products to services. Nouns will morph into verbs. The shift from “ownership that you purchase” to “access that you subscribe to” overturns many conventions.17 Instead of purchasing an individual book from Amazon, I can subscribe to Kindle Unlimited and read almost anything. Instead of purchasing an iTunes album, I can subscribe to Apple Music and listen to almost anything. Instead of purchasing a car, I can subscribe to GoGet and use a car whenever I like. And the list goes on. If you can purchase it, chances are that you can also rent it somewhere.

Accessing in the AEC industry

Accessing has multiple implications for the AEC industry. At a basic level, we’re witnessing an increasing shift from perpetual licensing to subscription licensing in design technology software. Unlike the unlimited access subscriptions offered by Kindle Unlimited or Apple Music, Autodesk software subscriptions have brought minimal material benefit to the end user. Yes, users have access to multiple software versions, but for all intents and purposes, the product remains identical to what we would have purchased via a perpetual license. However, if we reframe our thinking and consider access in the context of a microservice instead of software, we can see how access will fundamentally change how we work.

Whereas previously, only large organisations could afford to develop and reap the benefits of automation, access that you subscribe to lowers the entry barrier by democratising knowledge. For example, our entire Dynamo Package can now be streamed via subscription, enabling smaller organisations to compete with larger ones.

Further afield, we’re witnessing large chunks of a project being automated via third-party subscriptions—discrete workflows automated by others but implemented into your projects. Think mass-timber generators, car park generators, stadium generators, and solar farm generators. The list goes on. Simply hire the module for the duration you require. Autodesk’s Forma is already making a play in this space via various integrations with third-party generators.

Business model adaption

This technological force is more profound than merely a different way of paying for software. It will fundamentally challenge AEC business models. For example, if every organisation has access to affordable automation, domain expertise may cease to be necessary. Why hire someone with years of domain expertise when you can simply hire an algorithm? Moreover, organisations will be forced to find new ways to differentiate themselves. Instead of inputs (time-based) or deliverables (output-based) pricing, the industry may be forced to price on outcomes (value-based pricing). As accessing becomes more and more prominent, AEC organisations will be forced to adapt their existing business models.

#6 Remixing

All new technologies derive from a combination of existing technologies. As Isaac Newton famously said, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” The quote highlights that new discoveries and insights are rarely made in isolation. Instead, they are usually the result of cumulative knowledge and advancements made by previous generations.

Remixing is the rearrangement and reuse of existing pieces of knowledge or technology, and it can be seen in all facets of life. Consider the author who dips into “a finite database of established words, called a dictionary, and reassembles these found words into articles, novels and poems that no one has ever seen before.”18 These words may then be unbundled and remixed to create a 280-character tweet. This tweet may then be unbundled, remixed and recombined to create an animated GIF. Through this process of remixing, new media genres are born.

Central to remixing is the concept of non-destructive editing, the ability to rewind to any particular previous point you want at any time and restart from there, no matter how many changes you’ve made.19 This re-do function encourages creativity and can be seen in Wikipedia or Google Docs, where all previous versions are kept and easily re-established. Or consider Adobe Photoshop, which enables adjustment layers for non-destructive adjustments to the original image.

The primary bottleneck for a non-destructive design paradigm is computation. Destructive editing only needs to save the result of an edit, without recomputing the entire graph. Non-destructive editing, on the other hand, must store the inputs and continually compute any downstream results.

Remixing in the AEC industry

Remixing is one of the most potent technological forces transforming the AEC industry, and its trajectory is coupled with the history of computation. During the 2D drafting era, commercially accessible software such as AutoCAD adopted a destructive paradigm, meaning that only the result of an edit or modification was stored. As the industry progressed into the 3D modelling era, we saw the introduction of non-destructive editing. For example, 3D Studio Max enables modifiers to be applied to an object, modifying its geometry or properties. These modifiers are stored in a stack to control the sequence of modifications. Similarly, McNeel Rhinoceros contained a feature called explicit history, to enable the output geometry to be updated based on the inputs.

As the industry transitioned into the Building Information Modelling (BIM) era, we began to see more non-destructive editing. In Autodesk Revit, once an element is modelled, its type can be easily changed. For example, a wall’s thickness can be easily updated without needing to delete the wall and remodel it. However, while BIM enabled non-destructive editing for individual elements, it wasn’t until the Design computation era that entire buildings could be edited non-destructively. Here, the designer no longer directly models the building: instead, they develop a script whose execution generates the model.

Towards BIM 2.0

Within the AEC industry, there is a push for web-based software, so-called BIM 2.0. This push mainly stems from user frustration with the lack of development of existing BIM software, namely Revit. However, if you look under the hood at most web-based software, the technology stack is primarily comprised of legacy software, namely Rhino and Grasshopper, but remixed with a database and a web-based user interface. The benefit of the software is not that it is new software – all new software is built upon existing software – but rather its ability to enable non-destructive editing at scale via cloud computing. Remixing, via non-destructive editing, will enable the rapid exploration of entire buildings, not just individual elements.

Conclusion

Becoming, cognifying, flowing, screening, accessing and remixing – these are the six technological forces shaping the AEC industry’s future. Becoming demonstrates how fostering a culture of learning will be more important than hiring an expert. Cognifying will force us to re-evaluate what it means to be a professional. Flowing will see technological infrastructure liquefy. Screening will afford a more comprehensive understanding, not just a snapshot of it. Accessing will force the adaptation of existing business models. And remixing will enable the rapid exploration of entire buildings via non-destructive editing. By understanding these forces, AEC organisations can better prepare for their future. Ignore at your peril.

References

1 Day, M. (2 Jun 2023). Defining BIM 2.0. In AEC Magazine.

2 Future AEC Software Specification.

3 Day, M. (10 Feb 2022). BIM is bust: How should AEC data work? In AEC Magazine.

4 Germain, T. (18 May 2025). Still booting after all these years: The people stuck using ancient Windows computers. In BBC.

5 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.11.

6 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.13.

7 Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Penguin Books, London, p.40.

8 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.29.

9 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.59.

10 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.47.

11 Carpo, M. (2017). The second digital turn: Design beyond intelligence. MIT Press, Cambridge, p.25.

12 Aristotle. The Organon 1: The categories on interpretation: Prior analytics.

13 Weinberger, D. (2014). Too big to know: Rethinking knowledge now that the facts aren’t the facts, experts are everywhere, and the smartest person in the room is the room. Basic Books, New York, p.11.

14 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.85.

15 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.94.

16 Goodwin, T. (4 Mar 2015). The battle is for the customer interface. TechCrunch.

17 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.112.

18 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.200.

19 Kelly, K. (2017). The inevitable: Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penguin Books, New York, p.206.

5 Comments

Ross Andrew

Great

Paul Wintour

Thanks Ross. Glad you enjoyed it.

OWEN DRURY

good article Paul

Paul Wintour

Thanks Owen. Hope you are well.

Michał

came here to find something about dynamo and instead I’ve read this article …

and it’s really good! thank you!