Within modular construction, the problem of how to build better is often framed in binary terms – construction versus manufacturing. You are either with us or against us. Enlightened, or part of the Dark Ages. Or, to use their parlance, we must modernise or die. Group polarisation at its finest.

Through this binary view of the world, we see a mirror of modern society: a world of alternate facts, half-truths, misinformation, disinformation, groupthink, marketing hyperbole, false narratives, and conflicting truths. When does a company vision, which is not yet attainable, stop being a Big Hairy Audacious Goal and become a flat-out lie? What separates evangelicalism from a half-truth? And most importantly, how can two views of the world be held as gospel, but be totally incompatible?

Since publishing our Modular construction & its Henry Ford Syndrome and Rewriting modular construction’s shitty first draft articles, modular construction has continued to have more drama than a Married At First Sight dinner party. So what’s changed, and how can we move beyond this binary way of thinking about industrialised construction?

Modern Methods of Construction – what’s gone wrong?

It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma…

Winston Churchill, 1939

So dire were the recent results of the UK’s Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) framework that in October 2023, the government launched a public inquiry.1 Over two months, the Built Environment Committee at the House of Lords heard from various industry professionals. While no Game of Thrones, the evidence sessions were fascinating, delving into MMC’s multiple facets and complexities.

Session 1 (24/10/2023) – Michael Stirrop (Vistry Group) & Carl Leaver (TopHat).

Session 2 (14/11/2023) – Dr Suzanne Peters (The University of Manchester) and Professor Jonatan Pinkse (The University of Manchester).

Session 3 (20/11/2023) – Andrew Wolstenholme (Laing O’Rourke), Christy Hayes, (Vision Modular Systems and Tide Construction) and David Jones (Elements Europe).

Session 4 (29/11/2023) – Mervyn Skeet (Association of British Insurers), Richard Smith (National House Building Council), and Matthew Jupp (UK Finance).

Session 5 (5/12/2023) – Katie Gilmartin (Platform Housing Group), Craig Garbutt (Daiwa House Modular Europe UK), and Nicky Jones (Daiwa House Modular Europe UK).

Session 6 (12/12/2023) – Lee Rowley MP (Minister for Housing), David Bridges (Homes England), and Edward Jezeph (Homes England).

A key catalyst for the inquiry was undoubtedly Homes England’s investment and subsequent loss of £68m of taxpayers’ money after Ikle Homes went bust in June 2023. Surely, lessons were learnt, and the same mistake wouldn’t be repeated. Not quite…

TopHat

The first evidence session saw Carl Leaver, Chairman of TopHat, dispel doubts and reassure the committee that their business model was sound. He then, however, lamented the lack of financial support from the UK government: “Nissan built their factory in the UK with hundreds of millions of pounds worth of government support. We have had none. We are trying to change a whole industry with private money”.2 One month later, Homes England saddled back up to loan TopHat £15m.3 This was even though TopHat had yet to turn a profit and lost £20.4m just last year.4

To add insult to injury, the loan was to fund a new 60,000 m2 (650,000 ft2) factory in Corby, capable of manufacturing 4,000 homes a year, compared to 800 in its current Derby facility. Yet despite the factory being almost complete, its opening has been put on hold, with a spokesperson for TopHat saying: “The short term market conditions mean it is prudent to pause now with the building almost complete but no equipment yet on site. We continue to develop our pipeline and will monitor conditions closely to restart when it is right to do so.”5

The news comes just a few weeks after TopHat started a round of redundancies as part of a cost-cutting drive with around 70 jobs under threat. Not long after, TopHat’s Managing Director, Andrew Shepherd, announced he was “stepping down amid an ongoing streamlining programme.”6 Despite trading for eight years, and with the benefit of over £200m in funding, TopHat has yet to make a profit and continues to hemorrhage cash to the tune of £20m per year. It is not hard to read the writing on the wall. TopHat’s days are clearly numbered.

Lights out at Lighthouse

In March 2024, UK timber-framed volumetric modular builder Lighthouse, previously known as IDMH, went into administration owing £14.9m to creditors.7 Lighthouse had recently partnered with BoKlok, a joint venture between IKEA and Skanska, to construct four-storey apartment blocks in South England, which ran twelve months over schedule. Ironically, just four months earlier, Lighthouse submitted written evidence to the UK inquiry to distance themselves from other failed companies, claiming that the collapse of volumetric modular builders was due to “company-specific issues”. They argued:

Growing a volumetric modular manufacturing business is a very challenging endeavour, as demonstrated by the number of high profile closures within the sector. These closures further demonstrate that, although positive sectoral developments continue, no volumetric operator has successfully achieved a profitable, scaled business model yet. It is worth stating however that we believe certain closures resulted from company-specific issues, not just macro factors, and such closures are not necessarily representative of general sectoral impediments.8

A statement from administrators claimed that: “[Lighthouse] has suffered cashflow pressures in recent months and efforts to secure a sale of the business and assets has unfortunately been unsuccessful.”9 The term cashflow pressures, of course, is business gobbledygook for a lack of project pipeline, or to put it more bluntly, a lack of demand. Whichever way you phrase it, it is a recurring theme that many MMC organisations succumb to.

Beattie Passive

In an eerie parallel with Lighthouse, UK modular builder Beattie Passive, who created net zero Passivhaus houses, also filled for administration in March 2024. The cause? You guessed it – cashflow problems. These problems arose “due to delays in the company’s biggest house building projects” despite having a forward order book worth £4.5m.10

Viridi

In April, Australian modular builder Viridi Group went into administration. Established in 2020, Viridi Group delivered timber-based, pre-finished structural modules. According to the company, a freeze on a major government-backed project disrupted its operational momentum. Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Ben Nurmi said, “The factory was set up to deliver certain products, and we were halfway through that contract when we got advice it would be suspended.”11

In many ways, this is Viridi’s second time round. Less than six years prior, former Virdi CEO Adam Strong succumbed to the same issue with his offsite timber business, Strongbuild, which went into administration in 2018. Strong attributed the failure to Frasers Australia pulling out of a contract just two weeks from commencement.12 Once again, the words of George Santayana ring true: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned repeat it.”

CLOS

It’s not a lie if you believe it.

George Constanza, Seinfeld

In a move to inspire confidence and distance themselves from the troubles facing others, marketing machines kicked into overdrive. Trade press Build Offsite, for example, ran the headline, “1,000 modular homes manufactured annually on CLOS’s calendar,” to promote Australian modular builder Cross Laminated Offsite Solutions (CLOS). In the article, CLOS makes various chest-thumping statements about how their new advanced automation line would produce up to 1,000 homes a year and how the company aimed to increase its staff to 100 by the end of the year.13 Onwards and upwards, or so we were led to believe.

Seven days later, the same media outlet announced that CLOS had entered into administration.14 Seven days. Either that was a really bad week for them, or we weren’t told the whole truth. It is possible that CLOS could build up to 1,000 homes a year and aimed to increase its staff. But this is a half-truth in the same way as Lance Armstrong saying, “I’ve been tested 500 times, and I’ve never failed a drug test.” Elements of truth while being completely deceptive. The decision to enter voluntary administration was attributed to high capital expenses and project cost blowouts.

Veev

On the other side of the Pacific, US-based Veev, which developed a closed-wall system, announced in November 2023 that it was shutting down due to the “abrupt cancellation of a capital-raising initiative.”15 This was despite having raised a total of US$600m. US$400m of which was secured as recently as March 2022.

Much like the UK inquiry, many US-based modular organisations were quick to distance themselves from the failed company and quickly clicked into evangelical mode. However, rather than attributing it to company-specific issues, the arguments focused more on the fact that Veev wasn’t technically a (volumetric) modular company as portrayed by the media. But this seems like country-specific semantics that miss the point. Volumetric, or non-volumetric. It doesn’t matter. Of more importance is the fact that, once again, the pitfall of large upfront venture capital has come to the fore. As one commentator summed up:

Solving American residential construction’s labour and talent constraint, affordability crisis, and building quality, resiliency, and sustainability challenges are five to 10-year projects. They don’t square up with venture capital investment cycles. They won’t obey Silicon Valley start-up rules of engagement for legacy industry disruption. Patience, perseverance, and discovery are non-negotiables that need to ride along with the applied brilliance of innovators.16

But Veev was not the only one who fell victim to the drying up of venture capital to fuel their viability.

Modulus

Just one month earlier, in October 2023, Modulous launched their digital design tool, Tech Enabled Solutions for Sustainable Architecture (TESSA), only to go into administration three months later in January 2024. Ironically, Modulous had previously described the business as nimble because it operated without a factory and “so doesn’t have a single point of failure.” Founded in August 2018, Modulus’ business model sounded promising – a software platform coupled with a physical kit of parts and a decentralised manufacturing process.

Yet, despite a substantial five years of effort and £17.5m in investment,17 the firm’s only client for its physical kit of components was a pilot scheme to construct 12 homes for Bristol County Council.18 In 2022, the company reported a staggering £9.5m loss, with a mere £91,000 turnover.19 Hardly a viable business model, no matter how you frame it.

Chief executive Chris Bone blamed Modulus’s downfall on “the vagaries of the venture capital markets”.20 He claimed, “It’s very difficult to satisfy venture funders with their appetite to get to revenue and grow quickly when the planning processes and all the usual inertia in the UK construction market prevents you from doing that effectively.”21

From unicorns to zombies

The challenges faced by Modulus and Veev were entirely predictable. In December last year, the New York Times reported on the drying up of Venture Capital (VC):

After staving off mass failure by cutting costs over the past two years, many once-promising tech companies are now on the verge of running out of time and money. They face a harsh reality: Investors are no longer interested in promises. Rather, venture capital firms are deciding which young companies are worth saving and urging others to shut down or sell. It has fueled an astonishing cash bonfire… approximately 3,200 private venture-backed U.S. companies have gone out of business this year, according to data compiled for The New York Times by PitchBook, which tracks start-ups. Those companies had raised $27.2 billion in venture funding.22

The boom in venture capital (and inflated valuations) was directly tied to ultralow interest rates that lured investors away from low yields on conventional investments to startups, which promised outsized returns. But like the Dot-com bubble that burst in early 2000, the glory days of VC are over. As the tech bust continues through 2024 and beyond, many more startups will fail. It turns out that in the post-venture capital bonanza world, boring things like turning a profit and having a sustainable business model have become important. Who would have guessed?

Conflicting truths

After two months of evidence sessions, the Built Environment Committee at the House of Lords presented their final inquiry report. One of the key findings was conflicting truths:

[The committee was] told by housing associations, developers and the Royal Institute of Charted Surveyors that Category 1 [volumetric] housing is, or could be, more expensive than homes built using traditional construction methods, hence either needing public investment to offset the added cost or simply taking the decision to not use MMC. With the same level of certainty we heard that MMC homes are cheaper. These two statements cannot both be true.23

The report concluded, stating, “It is unclear why, if MMC brings the full range of benefits we have heard, the private sector is not providing sufficient demand to manufacturers.”24 In other words, if we are led to believe MMC does exactly what it says on the tin, why isn’t it working? And this is a valid question. After all, at the same time as the UK inquiry, it was revealed that three schools built by UK-based volumetric builder Caledonian Modular, who went into administration in March 2022, would need to be demolished due to structural defects.25 It is no wonder that the Built Environment Committee unearthed so many conflicting truths about MMC.

Big Hairy Audacious Goals

One explanation for the conflicting truths is the current startup funding model whereby the bigger the Big Hairy Audacious Goal (BHAG), a term popularised by Jim Collins to articulate a bold mission, the more interest from venture capitalists. Many VCs are completely transparent that they invest in individuals, not companies. They want founders to sell their vision of the future, even if that vision is not yet obtainable. Sometimes, the vision will motivate employees to make the impossible possible. Steve Jobs, for example, was known for his Reality Distortion Field. But at some point, evangelism becomes flat-out lies or, in extreme cases, fraud. Consider the alumni of many who have appeared on the cover of Forbes magazine.

Fake it till you make it

In 2021, Sam Bankman-Fried, founder of FTX cryptocurrency exchange, made the Forbes’ 30 under 30 list with an estimated worth of US$26.5b, making him the 64th richest person in the world. However, just recently, he was convicted of fraud, conspiracy, and money laundering and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

In 2019, Charlie Javice made the Forbes list. Her company, Frank, which helped students navigate the financial aid process, claimed to have over 5 million clients. However, earlier last year, she was charged for “falsely and dramatically inflating the number of customers of her company” to get JPMorgan Chase to acquire the company. According to the lawsuit, Frank only had about 300,000 clients and fabricated data to show a larger customer base.26 Javice has denied all the allegations against her and is awaiting trial.

In 2017, Adam Neumann, co-founder of WeWork, appeared on the cover of Forbes with the headline: “WeWork’s $20 Billion Office Party”. Neumann had sold investors of his vision to “elevate the world’s consciousness”, and by 2019, the company was valued at an eye-watering US$47b. But as part of their Initial Public Offering (IPO), WeWork was required to disclose its financials. The backlash was quick and lethal, with US$39b wiped from its valuation almost instantaneously. WeWork never recovered, and in November 2023, they eventually filed for bankruptcy, becoming supernova stardust.

In 2015, Forbes hailed Elizabeth Holmes the youngest and wealthiest self-made female billionaire in the United States based on a US$9b valuation of her company, Theranos. The company claimed that it had devised blood tests that required very small amounts of blood and could be performed rapidly and accurately, all using compact automated devices that the company had developed. However, these claims were proven to be false. Holmes was convicted of defrauding investors and sentenced to 11 years in prison.

It is clear that in the startup world, faking it till you make it is still very much real. Why would modular construction be any different?

Unified theory of everything

The other explanation for MMC’s conflicting truths is that both viewpoints are partially true but incomplete. Take, for instance, general relativity (gravitational forces) and quantum mechanics (non-gravitational forces). Both theories have been validated. However, the two theories are considered incompatible in regions of extremely small scale – such as those that exist within a black hole or during the beginning stages of the universe. In physics, the Theory of everything seeks to unify these theories into a singular, all-encompassing, coherent framework of physics that fully explains and links together all aspects of the universe.27

Modular construction promises economies of scale given sufficient volume. This truth holds once a certain critical mass is achieved. But below this threshold, the laws of modular construction break down and traditional construction reigns supreme. What exactly is this threshold is anyone’s guess. But given that most objects are manufactured in the millions, not the thousands, I suspect modular construction is some way off to achieving the critical mass it needs. Of course, this will not put off the countless modular startups trying. Time and time again, we witness modular’s resolute and unwavering aversion to considering alternative approaches.

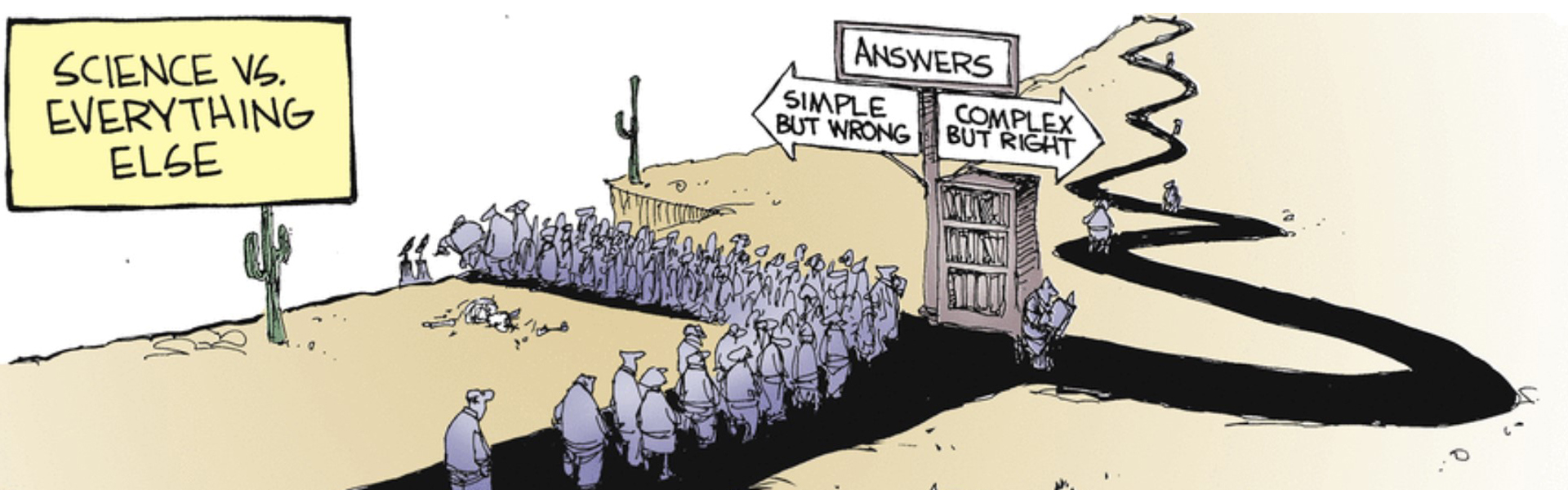

Bursting filter bubbles

First, our wrong opinions are shielded in filter bubbles, where we feel pride when we see only information that supports our convictions. Then our beliefs are sealed in echo chambers, where we hear only from people who intensify and validate them.28

The problem of how to build better is almost exclusively framed in binary terms – construction versus manufacturing. A black and white issue with two sides pitted against each other. Consider a recent event titled, Is the future Modern Methods of Construction? Clearly, it was a rhetorical question as, unsurprisingly, every speaker said yes. There was not a single counter-argument. Of course, this was a sponsored event, so it was not unexpected.

The value proposition of MMC is clear. But so, too, are the realities that organisation after organisation are failing to make it work. Billions of dollars have been poured into failed modular ventures, many with super-intelligent people behind them and government intervention. But time and time again, they fail. If we continue to oversimplify the problem and drink the Kool-Aid, we’ll continue to get nowhere.

Towards intellectual curiosity

Binary bias is the basic human tendency to seek clarity and closure by simplifying a complex continuum into two categories. It presumes that the world is divided into two sides: believers and non-believers. Only one side can be right because there is only one truth. But like most things, industrialised construction is a complex problem with many shades of grey.

We must stop the binary thinking and develop intellectual curiosity about how we approach industrialised construction. Specifically, as an industry, we need to stop using how much money a company has raised as a proxy for defining success. Modular organisations are routinely celebrated as the next big thing despite not building a single building. And this is in the context of operating for four or five years, well and truly past the honeymoon phase. Is this really our definition of success? What matters more is effectiveness, but this requires deeper analysis than simplified binary thinking. If we continue to lack critical thinking, we’ll continue to see the same mistakes repeated over and over and over again.

Conclusion

Despite all the failure, marketing hyperbole, false narratives, and alternate facts, I still believe industrialised construction holds the answer to improving the AEC industry. Construction should be industrialised. It should be more efficient. But this can be achieved in any number of ways. We must see modular as a means that can be judged against others for its effectiveness in achieving its ends. And if it fails, we need to look at alternate means. And this starts by exploring alternate business models that hold true for all scales. Only then will we rid ourselves of our conflicting truths.

References

1 Build Offsite. (27 Oct 2023). UK government launches inquiry into Modern Methods of Construction following collapse of high-profile modular builders. In Built Offsite.

2 Built Environment Committee. (24 Oct 2023). Modern methods of construction – what’s gone wrong? House of Lords, London.

3 Prior, G. (22 Nov 2023). TopHat agrees £15m loan with Homes England. In Construction Enquirer.

4 The construction index. (8 Aug 2023). Volumetric builder still three years away from making a profit. In The construction index.

5 Prior, G. (26 Mar 2024). TopHat puts plans to open huge Corby factory on hold. In Construction Enquirer.

6 Morby, A. (9 May 2024). Modular builder TopHat managing director departs. In Construction Enquirer.

7 Build Offsite. (12 Apr 2024). Lights out at Lighthouse. In Build Offsite.

8 Lighthouse. (5 Dec 2023). Written Evidence.

9 Stein. J (11 Apr 2024). Staff made redundant as modular builder collapses. In Construction News.

10 Build Offsite. (29 Mar 2024). UK modular construction Beattie Passive files for administration. In Build Offsite.

11 Built Offsite. (19 Apr 2024). Modular builder Viridi Group in voluntary administration. In Built Offsite.

12 Perinotto, T. (15 Nov 2018). Strongbuild falls as Frasers Property pulls the pin on a major deal. In The Fifth Estate.

13 Build Offsite. (24 May 2024). 1,000 modular homes manufactured annually on CLOS’s calendar. In Build Offsite.

14 Build Offsite. (31 May 2024). CLOS enters voluntary administration, seeking recapitalisation to sustain operations. In Build Offsite.

15 Azevedo, M. (28 Nov 2023). Prefab home builder Veev reportedly shutting down after reaching unicorn status last year. In TechCrunch.

16 McManus, J. (1 Dec 2023). Veev falters: Lessons learned for homebuilding innovation. In The Builders Daily.

17 Modulus. In Crunchbase

18 Battersby, M. (10 Jan 2024). ‘It’s been a torrid time’: Modulous boss Chris Bone on the offsite housing firm’s collapse’. In Housing Today.

19 Battersby, M. (10 Jan 2024). Modular housing firm set to go into administration. In Building.

20 Battersby, M. (10 Jan 2024). ‘It’s been a torrid time’: Modulous boss Chris Bone on the offsite housing firm’s collapse’. In Housing Today.

21 Battersby, M. (10 Jan 2024). ‘It’s been a torrid time’: Modulous boss Chris Bone on the offsite housing firm’s collapse’. In Housing Today.

22 Griffith, E. (7 Dec 2023). From unicorns to zombies: Tech start-ups run out of time and money. In The New York Times.

23 Built Environment Committee. (26 Jan 2024). Modern Methods of Construction in housing. House of Lords, London, p.3.

24 Built Environment Committee. (26 Jan 2024). Modern Methods of Construction in housing. House of Lords, London, p.7.

25 Morby, A. (5 Dec 2023). Three Caledonian Modular-built schools to be demolished. In Construction Enquirer.

26 Mahdawi, A. (7 Apr 2023). 30 under 30-year sentences: why so many of Forbes’ young heroes face jail. In The Guardian.

27 Wikipedia contributors. (29 Mar 2024).. Theory of everything. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

28 Grant, A. (2021). Think again: The power of knowing what you don’t know. WH Allen, London, p.61.

29 Miller, W. (10 Aug 2020). Non Sequitur. GoComics.